Gisela Ernst-Slavit and Margo Gottlieb are changing the mindset for educating multilingual learners

Most education systems, despite their growth in numbers of multilingual students, still cling to monolingualism as an idealized pathway to language and literacy learning. As an extension, institutional ideologies tend to perpetuate the notion of academic language as a status symbol, bearing power that privileges standard varieties of English and treats standard language as the desirable norm in language teaching.

We propose shifting from a static, rather confined notion of academic language to a more dynamic view of academic languaging—language use that is flexible, dynamic, actionable, and, most important, in the hands of the learner. Language learning that then becomes sociocultural and interactive in nature, a social practice rather than a bound system.

Academic languaging invites multilingual students to be proactive learners by having opportunities to access their languages of choice and become agents of their own learning. Ultimately, when we speak of academic languaging, we refer to the whole student and all their identities. In essence, we shift our conceptualization of language from a tacit noun to an active verb so that all educators view academic languaging as an ongoing process that draws from and centers the lived experiences of students and their interactions with others, technologies, and multimodal text forms.

Since our academic language series (Gottlieb and Ernst-Slavit, 2013, 2014) over a decade ago, we have emphasized that academic language extends beyond school and content-area knowledge to include family, community, and cultural knowledge. In fact, we maintain that language learning requires more than linguistic knowledge—it also encompasses cultural knowledge, the “ways of being in the world, ways of acting, thinking, interacting, valuing, believing, speaking, and sometimes writing and reading, connected to particular identities and social roles” (Gee, 1992, p. 73). In this article, we share the evolution of our thinking on the nature of language use and learning to embrace academic languaging. In it, we 1) speak to the advantages of academic languaging as a stance or a mindset as well as a means of communication; 2) suggest how to infuse academic languaging into curriculum through model texts; and 3) offer examples of academic languaging across content areas.

Academic Languaging: A New Way of Thinking

Any educator who has studied language education since the 1980s has likely encountered Jim Cummins’s concepts of basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) and cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP). This false dichotomy of social versus academic language has dominated education, offering a practical (yet misleading) way of differentiating informal, everyday registers as precursors to more formalized, literacy-dependent ones. Unfortunately, social language has often been undervalued, despite its academic relevance and potential as part of a student’s learning experience.

When taking a more dynamic, action-oriented stance of language that relays a specific message, has a specific purpose, and relates to a specific audience to effect change, we use the term languaging. Action-based teaching promotes student agency, along with the development of self and identity (van Lier, 2007). Looking at the following examples, which of the instructional activities represent academic languaging?

- Comparing three personal experiences to those of the three bears.

- Explaining how to design a playground for your school.

- Observing chickens laying eggs to sell at local markets.

- Describing the significance of el Día de los Muertos to Mexican families.

The answer—each instance can be considered one of academic languaging, as it is tied to a meaningful action where students are potentially engaged participants in the (co)construction of knowledge shaped by social and cultural factors. Each option includes some form of inquiry-based learning and is influenced by students’ personal cultural insights across content areas. With an action-based orientation, multilingual learners determine, engage in, and reflect on their learning through research, projects, and presentations that pique their interest. Language development is fostered through student interaction in planning, exploring, and collaborating on varied activities.

Academic language is often equated with vocabulary—learning content-specific words at designated tiers for a lesson or unit. Academic languaging, however, embraces multiple layered dimensions of language, starting with discourse and encompassing sentences, word/phrases, and symbols. Yes, symbols—representations of culturally related nuances (e.g., money denominations, Roman numerals) with specific meanings, applications, and actions (or nonactions, like a stop sign). There are symbols connected to multi-modal messaging, digital media, and content areas, such as those in the figure below.

Figure 1. Selected symbols connected to content-area learning (Ernst-Slavit and Gottlieb,2025, p. 18)

When speaking of language development as a student’s increasing range and depth of language use, we often overlook the full resources multilingual learners bring to the learning situation. Academic languaging ideally gives students freedom to utilize all their linguistic repertoires, pursue learning in languages of their choice, and engage in translanguaging. With a

greater range of languages at their disposal, multilingual learners can cast away the deficit thinking that has surrounded their persona and gradually move toward greater autonomy in learning.

Adopting an academic languaging mindset means valuing the language practices of students, teachers, and communities while recognizing that language is constantly being shaped and reshaped (think about how AI has changed our use of language). Shifting from language to languaging moves us away from prescriptive, fixed, exclusive notions to more flexible and culturally sensitive ones. Our view of academic languaging offers a more favorable, more egalitarian perspective that counters criticisms that leverage academic language as:

- Learning a set of static linguistic forms (e.g., Flores and Rosa, 2015)

- Privileging standard White linguistic practices (e.g., Paris, 2012)

- Being more complex and of higher status than other registers (e.g., MacSwan, 2020)

- Serving as a tool for segregation and exclusion (e.g., Jensen et al., 2021).

We hope to show you the value of academic languaging as a way to empower educators and multilingual learners by re-imagining the contexts and purposes for students’ language use by drawing on their linguistic and cultural experiences inside and outside of school. In short, now is the time to re-envision language development as a social, collaborative, and communicative process, deeply intertwined with having students take ownership of their learning, express their

own ideas, and interact with the world (Zwiers, 2025).

Exemplifying Academic Languaging Through Model Texts

Academic languaging can be enacted through model texts, examples that illustrate the features, structures, and expectations of target texts for students to access or produce. Model texts can be purposefully created by teachers to highlight genre characteristics or drawn from authentic classroom materials such as textbook excerpts, literature, or extended assignments. In both cases, model texts help educators and students examine how language works in context and promote students’ active participation in the process.

When teachers analyze these texts—especially with attention to their linguistic and cultural aspects—they can identify areas needing potential clarification or additional support, particularly for multilingual learners. This process not only aids students in understanding and producing similar texts but also helps teachers become more intentional about the language demands embedded in their materials and how students’ talents and experiences can support comprehension.

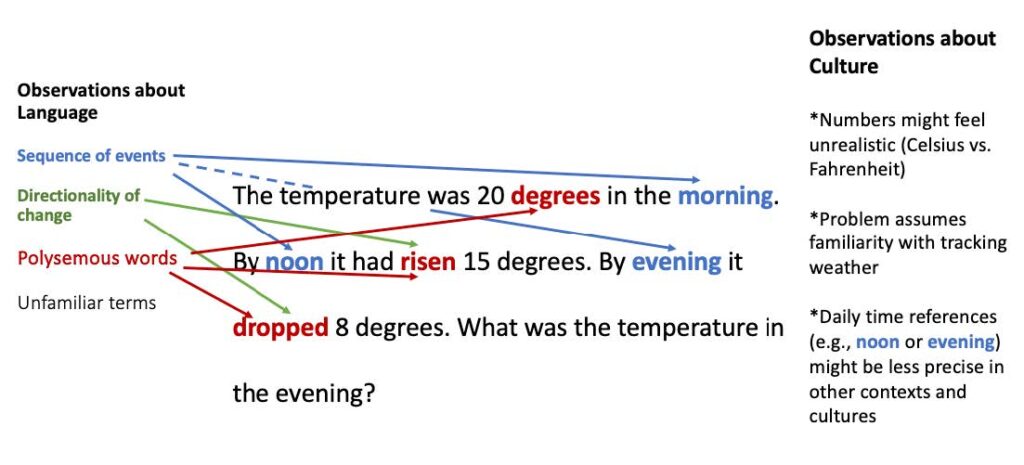

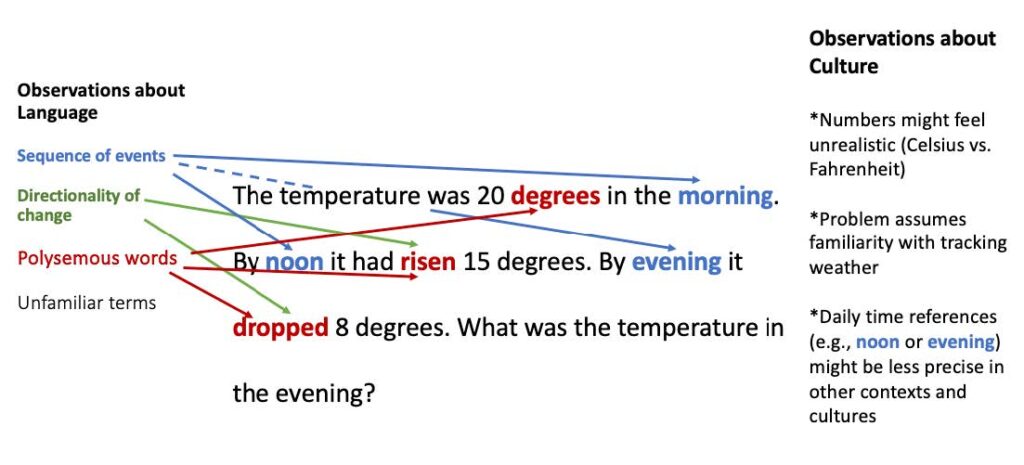

Consider a common feature of math classrooms: the story or word problem. Beginning in the early grades, students are asked to read these text-based problems—and they can be deceptively difficult. Often, it’s not the math that trips students up, it’s the language. The following problem was designed for second or third graders. As you read it, note areas that might be linguistically and/or culturally puzzling, especially for multilingual students.

The temperature was 20 degrees in the morning. By noon, it had risen 15 degrees. By evening, it dropped eight degrees. What was the temperature in the evening?

Although this looks like a simple addition/subtraction problem, multilingual students may face both linguistic and cultural challenges in making sense of it, as shown below.

Figure 2. Linguistic and cultural challenges in a story problem

Linguistic Challenges

- Final question wording. “What was the temperature in the evening?” requires holding the sequence in memory and connecting it back to the original value.

- Implicit math language. The problem does not explicitly say “add 15” or “subtract eight,” so the student has to infer the operations from words.

- Sequence of events. The problem is structured in three time points (morning, noon, and evening). Students must track changes step by step across sentences.

- Directionality of change. Risen (increase) and dropped (decrease) require understanding of verbs, not just numbers.

- Vocabulary. Words like temperature, degrees, risen, and dropped may be unfamiliar or differ in everyday use.

Cultural Challenges

- Concept of temperature in degrees. Celsius users may find changes unre-alistic.

- Everyday experience with weather. Students from consistently hot or con-sistently cold climates may not relate to daily fluctuations.

- Language around time of day. The terms morning, noon, and evening vary culturally and may lack precision. For instance, in some Mediterranean countries, noon or medio día can refer to a three-hour period beginning at twelve o’clock, while in the US it refers to twelve o’clock.

- Assumptions. The problem presumes familiarity with tracking and discussing weather patterns.

While the math itself is straightforward—20 + 15 – 8 = 27—the language demands (sequencing, implicit math terms, imprecise vocabulary) and cultural assumptions (degrees, weather patterns, time references) can complicate the problem for multilingual learners. The point is not that teachers must dissect every word problem they assign, but rather that they should be aware that many math story problems assess language as much as mathematics. For strategies on supporting multilingual students with story problems, see Ernst-Slavit and Gottlieb (2025) and Ji-Yeong and Stanford (2018).

For fluent speakers, language often feels like air—we barely notice it. For multilingual learners, it can feel like an extra puzzle on top of already demanding schoolwork. Every subject has its own “language rules”—special formats, grammar, symbols, and ways of talking that are not always obvious. Pauline Gibbons (2002) reminds us teachers need to look at language, not just through it. And it’s not only big words—it’s idioms like “learn by heart,” slang, or cultural references that throw students off. That’s why it’s so important to be aware of the language we use, to slow down, explain, and give students time to play with language together. When we do, we’re not just teaching content—we’re giving students real tools to use their voices with confidence… and with this added assurance, multilingual learners can venture into academic languaging.

Just as model texts help teachers analyze the language demands of class-room materials, looking closely at students’ writing offers insight into their strengths—in English, in other languages, and through translanguaging—and pinpoints needed support. As you read this writing sample from Enrique, a second grader, consider:

- What strengths does this student exhibit?

- How can we nurture this student’s language development?

Biz are vare blak and vare yalow

thare fase is funny and they are makeing

Honey to?

Enrique’s writing shows clear strengths:

- Content knowledge: Familiarity with bees (appearance, behavior, honey-making).

- Sentence structure: Multiple complete sentences.

- Voice and engagement: Humor and personal perspective (“thare fase is funny”).

- Use of conjunction: And to connect ideas.

- Vocabulary variety: Descriptive words—blak, yalow, funny, honey.

- Phonetic spelling skills: Spelling based on sound correspondence (biz for bees, fase for face), showing awareness of letter–sound relationships.

Enrique’s description of bees and their actions reflects expanding vocabulary and growing content knowledge. Below are selected culturally sustaining strategies to support both language and content learning.

- Build on Enrique’s enthusiasm for science topics: Use videos, pictures, or local beekeeping visits to inspire writing or journaling.

- Use multilingual resources: Invite Enrique to share bee or honey terms and stories from his home language.

- Incorporate visuals: Use labeled diagrams of bees with colors, parts, and actions in a variety of spaces.

- Interactive writing: Co-create a bee fact chart as a class, modeling spelling while valuing phonetic attempts.

- Bridge oral to written language: Have students describe pictures or videos before writing in their choice of language.

- Celebrate risk-taking: Acknowledge creative spelling while modeling standard forms in a supportive way.

- Connect to community knowledge: Bring in family stories or artifacts to deepen engagement and relevance.

These strategies tap into Enrique’s full linguistic and cultural identities, honoring the ways he uses language and building on what he brings. Academic languaging here is not about learning a fixed, formal code. Rather, it is an agentive, ongoing process that focuses on students’ choices in using language for meaningful purposes.

Summary: Making Language Actionable When educators stop viewing language as something fixed—something to get “right”—we open up space for students to experiment, revise, and engage. We meet them where they are—drawing from what they already know, from home, community, and previous schooling—and we invite them to shape their learning in ways that are theirs. By framing academic languaging as an action, we’re giving language back to students. We’re saying: “This is yours. You get to use it, shape it, and express yourself through it.” That includes using all the languages they know. All the modalities they bring. And all the creative tools at their fingertips.

References: https://languagemagazine.com/refs-oct-2025-p30

Dr. Gisela Ernst-Slavit, professor emerita at Washington State University, grew up languaging in Spanish, German, and English. She has authored 13 books and over 100 articles and is a sought-after speaker who is passionate about empowering multilingual learners and the teachers who work with them.

Dr. Margo Gottlieb, co-founder and lead developer for WIDA at the UW-M, has authored or co-authored over 20 books and 100 chapters and articles and has designed an array of state assessment systems. In 2025, as a member of the inaugural class inducted into the Multilingual Education Hall of Fame, Margo was a recipient of a Multilingual Education Medal of Honor.