With increasing numbers of multilingual learners, representing over 20 languages and 65% of the student population, the expanded leadership team of administrators, teachers, and community members at the Marie Curie STEM campus determined that now is the time to revamp their educational system to be more responsive to the strengths of their students. The campus is now committed to:

- Investing in comprehensive schoolwide professional learning around evidence-based, data-informed instructional practices that embrace a multidimensional approach to assessment;

- Prioritizing collaborative, integrated models of instruction that support these assessment practices and establishing lab classes in select grades to begin incremental implementation.

For the first initiative, all teachers formed and participated in communities of practice (CoP), jointly deciding on a local problem of practice protocol. The bimonthly CoP sessions focused on revisiting and revising current assessment practices. Specifically, the agreed-upon goal was to clarify and refine the formative/summative distinction so that classroom assessment would become indistinguishable from and better inform instruction.

Like the Marie Curie campus, in this article, we examine the duality of “formative” and “summative” that tends to pervade educators’ view of assessment practices and argue to replace it with a more humanistic collaborative vision. To convince you of the benefits of seeing collaborative assessment as a learning experience, we outline the assessment cycle, emphasizing the often-neglected role of student participation. With students viewed as active agents in their own learning, assessment can become seamlessly embedded into instruction to spark a spirit of interdependence and co-learning, thus enabling classrooms to be supportive communities of practice.

Abandoning the Formative/Summative Dichotomy for Collaborative Assessment

Assessment is frequently described in dichotomies: formative versus summative, formal versus informal, standardized versus criterion-referenced, even graded versus ungraded. To best support students at the Marie Curie Campus and all multilingual learners, we are challenging you to shift to a tripart approach to assessment, one that highlights students’ strengths and assets; honors their lived experiences; nurtures their natural curiosity; fosters collaboration with other students, teachers, and families; and provides an equitable platform for meaningful data collection and use.

Together, three approaches—assessment as, for, and of learning—create a more balanced system that centers students and teachers (Gottlieb, 2016):

Assessment as learning is a student-driven process that enhances their motivation, engagement, and confidence in learning. Students are given ample opportunities to gain insight into their own thinking, feelings, and understandings through self-reflection as well as to engage in peer support, collaboration, and shared reflection on their learning.

For multilingual learners, assessment as learning is directly connected to their self-advocacy and identity formation: students must develop the skills and courage to advocate for themselves and embrace an asset-based rather than deficit-oriented perspective of their own development.

Assessment for learning is a process of making sense of the teaching–learning cycle. Through a dynamic, iterative process, educators and students gather and closely examine data to determine what is going well and what needs to be adjusted as teaching and learning unfold. Through this cycle, goals and objectives (or learning intentions/learning targets) are established and evidence for learning is negotiated.

For multilingual learners, assessment for learning revolves around an allegiance between students and teachers. Characterized by reciprocal feedback, assessment for learning allows for progress monitoring of students’ academic, linguistic, and social–emotional development while interacting with and supporting all students.

Assessment of learning contributes to determining student growth over time. At critical points, such as at the end of each unit of study, each trimester or semester, or each year, students are offered opportunities to demonstrate their newly developed knowledge and skills in comprehensive ways. Ranging from traditional paper and pencil tests with short constructed responses to essays, digitized adaptive tests, or extended projects, assessment of learning may take many different formats and modalities.

Assessment of learning assists in building students’ ability to tackle challenges and succeed on comprehensive tasks. Long-term projects invite students to dive deeply into learning. Successful completion of these tasks and projects leads to increased self-confidence in meeting rigorous standards. The results from assessments of learning help teachers understand students’ areas of strength and areas for growth.

The three approaches to assessment, summarized in Figure 1, revolve around building trusting relationships among the users. In reconceptualizing assessment as a more collaborative human endeavor, we view it as indispensable from learning. In seeing assessment as, for, and of learning, we can no longer envision it as a set of formative and summative practices but as a space for nurturing relations.

Figure 1: Humanizing Assessment as, for, and of Learning

| Assessment Approach | Building Relationships Between/Among | Examples of Collaboration |

| As learning | Students | Engaging in multilingual conversations around a learning target; deciding on a group assessment project |

| For learning | Students and teachers | Participating in student-led conferences; giving and acting on feedback |

| Of learning | Teachers with input from students and families; teachers and coaches; teachers and administrators | Agreeing on how to interpret success criteria; using data from multiple sources to decide next curricular and instructional steps |

Infusing the Co-Assessment Cycle into Collaborative Instruction

To successfully design, implement, and continually improve collaborative practices for serving multilingual learners, all members of your team must make a commitment to attend to the entire instructional cycle—co-planning, co-instruction, co-assessment, and co-reflection (Honigsfeld and Dove, 2019). None of these components exist in isolation or should be neglected. In our ongoing surveys, we have found that within the cycle, co-assessment is the least frequently implemented practice.

To optimize teaching and learning, the phases of the collaborative assessment cycle must work in tandem with the components of the instructional cycle. The interaction of the two cycles shows how information from assessment helps us to seamlessly advance collaborative instruction. With collaboration at the heart of both instruction and assessment, it seems rather divisive to try to parse assessment into a formative/summative distinction. Rather, as Clinton and Hattie (2024) say, “they can complement each other and sometimes work in parallel. It is not either/or, but when” (p. 15).

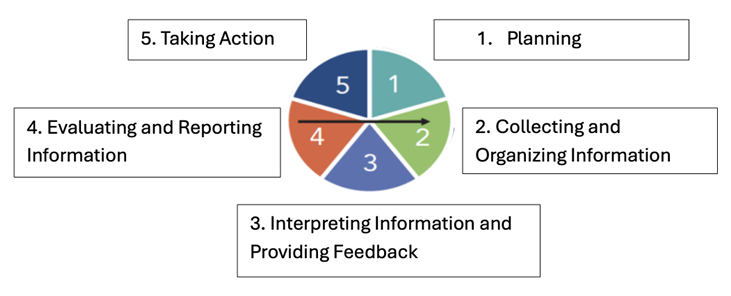

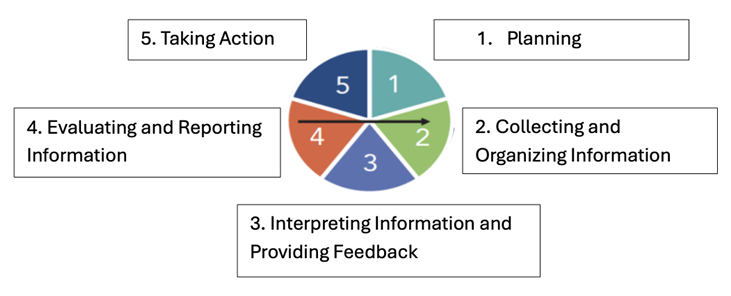

The five phases of the co-assessment cycle work in tandem with the three assessment approaches. Shown as a colorful spinner moving clockwise (see Figure 2), the cycle illustrates the “when” for assessment. Each phase (Gottlieb, 2021, 2022) marks a different source of student information for making instructional decisions. To the extent feasible, a collaborator, whether a teacher, student, administrator, or family member, helps inform the process.

Figure 2: The Five Phases of Collaborative Assessment

Phase 1: Planning

You might begin the collaborative assessment cycle with a team meeting between you and your students. In planning, with their teacher and peers, students co-construct their learning target or goal, whether for daily activities, weekly tasks, or long-term projects, and pair it with accompanying criteria for success, to personalize their learning experience (assessment for learning). This internalization of learning expectations and ways to accomplish them facilitates student agency and contributes to joint decision-making (Jones et al., 2024). When students also have opportunities to leverage multiple modes of representation, such as visually, kinesthetically, or orally, to demonstrate their learning, they can more readily share what they know and can do with others.

Phase 2: Collecting and Organizing Information

The more that you collaborate and agree on the kinds of information to be gathered, the stronger and more reliable the data become for instruction and classroom assessment. If teachers across a school or campus collaborate in deciding the kinds of entries in e-portfolios, for example, and apply linked descriptors, think of how much easier it becomes for you and your colleagues to agree on and communicate student progress (assessment of learning)

Phase 3: Interpreting Information and Providing Feedback

When interpreting information is a team effort and there is agreement between/among teachers, the data become more robust and meaningful across classrooms. At times, providing feedback might be between a student and teacher; at other times, it might rest on teachers working through a complex issue where in seeking a resolution, information must be pooled (assessment for and of learning). Throughout the assessment cycle, students also give feedback to each other based on evidence matched to their learning target or goal (assessment as learning).

Phase 4: Evaluating and Reporting Information

In the evaluation phase, teachers and/or students place a “value” or an appraisal on the extent to which their classroom and student targets and goals have been met and the best ways for communicating that information (assessment of or as learning). In reporting information, perhaps to students or other educators working with multilingual learners, you should always think about the most viable option; you may wish to translate the information for families and students, graph student growth with an accompanying explanation, or give personalized feedback to a student (assessment for learning).

Phase 5: Taking Action

Taking action, the final phase of the assessment cycle, has several applications depending on who is initiating it, whether students or teachers. For instance, students engaged in inquiry learning may pursue a real-life solution to their question, such as campaigning for an issue they have researched or taking their response to their principal (assessment as learning). For teachers, taking action might entail using the data with their professional learning community to formulate and defend a policy, such as the viability of translanguaging for assessment purposes or redesigning instruction to make it more linguistically and culturally relevant (assessment of learning).

Promoting a Culture of Collaborative Assessment

Recently we were struck by an article about a group of middle school students who insisted on knowing whether each of their assignments was formative or summative. For these budding teenagers, there was an acute difference between the two terms; a formative task was deemed unimportant and perceived as not counting whereas a summative one carried the weight of a grade. The students’ hyper-attention on what was to be “covered” and their focus on the outcome inhibited their desire to engage in authentic learning (Kuehn, 2022).

We might seem pedantic in our attempt to blur the lines between formative and summative assessment practices; however, how do we expect our students to become partners in collaboration and grow as learners when they are busy competing for a score or a grade? Going one step further, what can a student do who earns a C rather than a B, or how much has a student grown who receives an 82 and then a 91, or what does it mean to score 8 out of 10 correct? How would you justify those letters and numbers as indicators of student performance?

Clinton and Hattie (2024) plead to abandon the formative/summative distinction, claiming it has been inappropriately applied to and adopted by the assessment world, and to reinstate its original conceptualization by Michael Scriven (1967) as descriptive of educational evaluation. In a powerful statement, the two make the case to “abandon, expunge, and obliterate the notion of formative assessment.” We agree. It’s time to dismiss labeling the “how long or when” to distinguish formative from summative assessment and accentuate the “who,” the persons who engage in the process, collaborate with each other, and utilize assessment as, for, and of learning as a collaborative practice.

References

Clinton, C., and Hattie, J. (2024). “Revisiting and Expanding Scriven’s Fallacies About Formative and Summative Evaluation.” Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 20(47), 13–23.

Gottlieb, M. (2022). Assessment in Multiple Languages: A Handbook for School and District Leaders. Corwin.

Gottlieb, M. (2021). Classroom Assessment in Multiple Languages: A Handbook for Teachers. Corwin.

Gottlieb, M. (2016). Assessing English Language Learners: Bridges to Equity. Connecting Academic Language Proficiency to Student Achievement (2nd ed.). Corwin.

Honigsfeld, A., and Dove, M. G. (2019). Collaboration for English Learners: Foundational Strategies for Successful Integrated Practices. Corwin.

Jones, B., Faulkner-Bond, M., and Blitz, J. (2024). “Students Take Ownership over Their Learning with Formative Assessment.” Comprehensive Center Network, Region 15.

Kuehn, K. (2022). “The Way We Talk About Assessment Matters.” ASCD. www.ascd.org/el/articles/the-way-we-talk-about-assessment-matters

Scriven., M. (1967). “The Methodology of Evaluation.” In R. W. Tyler (ed.), Perspective of Curriculum Evaluation, American Educational Research Association, Monograph of Curriculum Evaluation, No. 1. Read McNally.

Margo Gottlieb has a PhD in public policy analysis, evaluation research, and program design (University of Illinois–Chicago), during which she first studied the work of Michael Scriven and other evaluation scholars. Their research has informed much of her thinking on assessment and its critical role in advancing learning for multilingual learners. Teaming with Andrea has given Margo insight into the critical role of collaboration in classroom assessment.

Andrea Honigsfeld, EdD, is professor at Molloy University, NY, where she teaches graduate courses related to cultural and linguistic diversity. She is an author/consultant and sought-after international speaker whose work focuses on teacher collaboration in support of multilingual learners. She is the co-author/co-editor of over 30 books, twelve of them bestsellers.

This article is based on Margo and Andrea’s bestselling book, Collaborative Assessment for Teachers and Multilingual Learners: Pathways to Partnerships (Corwin, 2025).