SELF-REGULATION IN SECONDARY SCHOOL CLASSROOMS

What happens when we allow students more freedom to regulate and organise their own revision before high-stakes exams? It’s not necessarily straightforward. James Harris reports on an initiative at Ibstock Place School in the UK.

Transferring responsibility

I have always found it difficult when pupils go on study leave before a set of big exams. They go from having their learning, classroom experiences, and homework heavily choreographed by me, to this study leave period characterised by a sudden shift to unstructured time and pupil-directed revision. Over the past few years, I have tried to channel this anxiety into something constructive, and I now ensure that when I am with my pupils, I am preparing them, not just for the exam, but to navigate those final weeks independently and as effectively as possible. Those timeless, overarching phrases – ‘learning to learn’ and ‘lifelong learners’ – spring to mind. As I dig a little deeper, self-regulation has surfaced as something I need to get to grips with, and something we are starting to ponder at Ibstock Place School.

SELF-REGULATION: THE THEORY

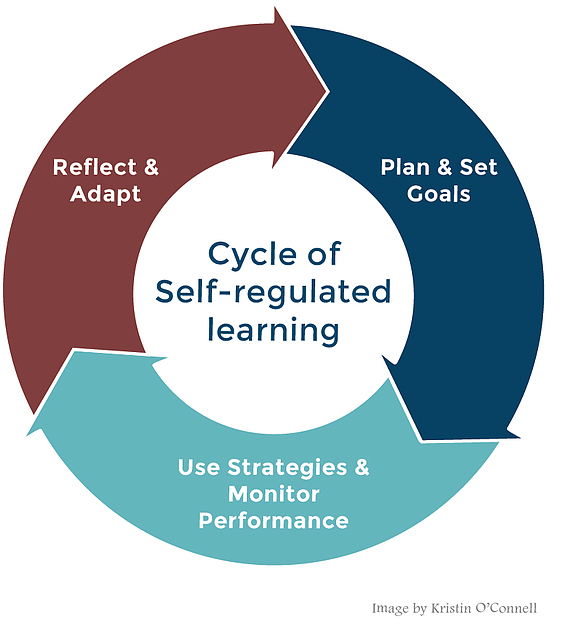

Self-regulation surged into prominence in the past decade fuelled by a wider pedagogical shift that is rightfully repositioning learners as active agents in their learning, rather than passive recipients. Pintrich (2000) defines self-regulation as the capacity to meaningfully reflect on one’s learning, and to subsequently optimise learning conditions in their favour. This is difficult to try and envisage in a typical classroom. Zimmerman (2000) proposes a three-phase cyclical framework for self-regulation with pupils setting goals, planning and monitoring progress and then evaluating outcomes to inform further goals. It seemed to me that Zimmerman’s approach mirrors the rhythms of summative assessment with a typical GCSE class: the revision and preparation, navigating the assessment itself, and the feedback and reflection. Spotting this link between routine practice and theoretical underpinning sparked a desire to investigate self-regulation further.

INVESTIGATING SELF-REGULATION

I wondered if, by granting my pupils scaffolded, structured opportunities to direct their own in-class revision and exam reflection (a significant step back from my usual hands-on didactic tendencies!) it could enhance the quality of their revision during study leave. I devised an intervention with my Y10 Geography pupils to gradually phase in pupil-led revision and pupil-led reflection opportunities, sandwiching our end of topic tests for a whole academic year.

Drawing on Panadero and Alonso-Tapia (2014), I ensured the pupil-led revision lesson was framed around developing revision resources that were tailored to a pupil’s way of learning and which they could hone and improve over time.

Meanwhile, I ensured the self-reflection was focussed on pupils thinking over exam preparation and revision, and not solely their exam score as is often the case. As well as recording exam performances during this intervention, I asked pupils to predict their assessment scores based on their revision, which I felt could act as a proxy of self-regulation (indicating pupils are in tune with how well they are learning). These numerical measures were accompanied with observational notes that I took during the lessons.

What happened

This is what I found:

- Less able pupils made more significant academic progress during the intervention, and I also observed that they made more noteworthy improvements in their engagement with the self-regulatory revision and reflections. It is possible that this is influenced by more able pupils already self-regulating to some degree, so the ability to see progress was less clear.

- A significant number of more able pupils found the increased freedom difficult and disconcerting, finding more confidence in teacher-led approaches. It was interesting to see my worries around study leave shared by some high achieving pupils.

- Pupils who made the most academic progress across the intervention had the least accurate predictions of their performance. This suggests that we cannot assume academic ability and progress necessarily triggers self-regulation. Equally pupils with self-regulatory capacities may not necessarily achieve the best academically.

- Female pupils appeared to adapt very quickly to the intervention, thriving with the increased freedom and benefiting as a result.

- Male pupils were much slower to embrace the freedoms, particularly around revision, however their scores and predictions did start improving when the self-regulatory intervention was well established.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Although, of course. this was a small sample, what happened in this class would seem to suggest the following:

- We cannot assume that pushing cohorts to be competent self-regulators will directly and promptly benefit all. Self-regulation competencies will resonate differently with different pupils, some relishing the increased autonomy and others resenting it, Subsequent benefits of self-regulation will likely be inconsistent across cohorts.

- However, self-regulation unquestionably has benefits for pupils beyond school and the classroom, and so there is some need for schools to facilitate it. For this to happen, self-regulation needs to be filtered in gradually and starting early in a pupil’s education, where they can grapple and reason with the process in a risk-free environment without looming exams.

- Because of this, self-regulation is best engaged with within schools but outside of settings with curriculum pressures. Self-regulation initiatives would be ideal as part of tutorial times, PSHE curricula, or critical thinking SOW, where there is greater scope for pupils to work at their own pace without an exam pressure to contend with.

ACTING ON THE FINDINGS

Ibstock Place is a restless school with a proudly restless Teaching and Learning agenda. Our weekly staff CPD keeps practice high on the agenda and always moving forward. Our Teaching and Learning Think Tank met in December to reflect on the self‑regulation study and consider how to integrate its insights meaningfully into our philosophy.

The first step was a Y7 “How Do I Revise Best?” study‑skills session on their tutorial day, and we are developing our target‑setting procedures so pupils can be more active and instrumental in their progress. We are also advancing our Compass Learning pedagogy, recognising that all pupils are different, with distinct journeys to success, each worth celebrating. We hope these steps will be the gradual, subtle nudges that take us closer to developing self-regulating pupils – or developing lifelong learners, as the saying goes.

James Harris – Director of Teaching and Learning at Ibstock Place School London

Feature & support images: With kind permission from Ibstock Place School & Kateryna Hliznitsova For Unsplash+

Graphics: Learners Who Self-Regulate Can – Eric Sheninger @ E_Sheninger.com – Image created by @ RigotRelevance, & Cycle of Self Regulated Learning by Kristin O’Connell

Further reading

Pintrich, P.R., (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of educational psychology, 92(3), pp. 544-555.

Panadero, E. and Alonso-Tapia, J., (2014). How do students self-regulate? Review of Zimmerman’s cyclical model of self-regulated learning. Anales de psicologia, 30(2), pp.450-462.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (Eds), Handbook of self-regulation, pp.13-39. San Diego: Academic Press.

The post RETHINKING REVISION appeared first on Consilium Education.