Dear We Are Teachers,

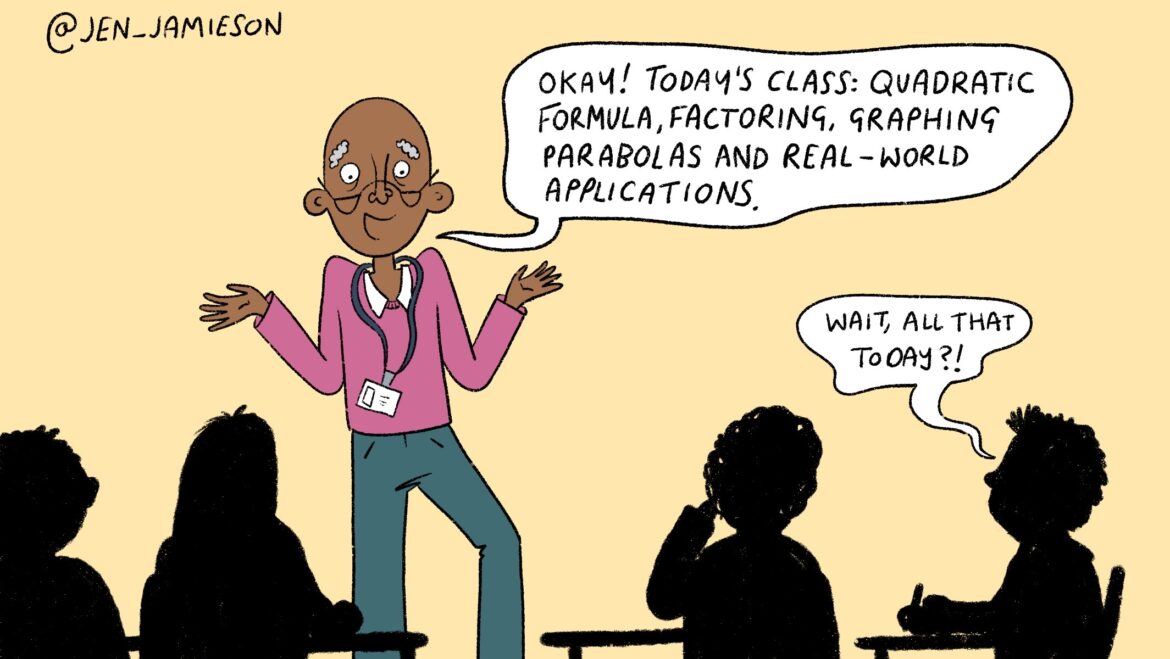

This year, our district rolled out a new curriculum with an aggressive pacing guide. I’m supposed to cover entire units in a matter of days, even though my students need way more time to grasp the material. I feel like I’m speed-running lessons, cutting corners, and leaving kids behind just to “stay on schedule.” It’s not how I want to teach, but I also don’t want to get in trouble for falling behind. How do I find a balance when the pacing guide is completely unrealistic?

—Racing the Clock

Dear R.T.C.,

Oh, my friend. I could have written this question myself. Specifically in the years 2010-2013.

My best advice? Start gathering your data now. Know exactly what you were able to get to, what you weren’t, and when. Then, when you check for understanding, gather that data too.

Present that data—and your suggestion for what you’d like to see—to a department chair or academic coach. “I’m concerned that this is what we were able to cover, and this was the result. Do you think I might be able to spend a little more time with my students on the more fundamental concepts and spiral in the more advanced learning later?”

That way, you’re not flopping on their couch and saying, “I can’t hack it! This is impossible! What do I do?” You’re presenting inarguable information and a plan to address it. (You’re also not waiting for someone else to discover this problem, which is a surefire way to not get a lot of sympathy.)

Save the couch-flopping for day 3 of standardized testing in the spring. You’ll need it.

Dear We Are Teachers,

I just started at a new school this year (my fifth in education overall) that “strongly encourages” quarterly “community service” for the school. You come in on a Saturday and can choose between outdoor activities like picking up trash, painting, landscaping and gardening, etc., or indoor activities like helping out in the library, sorting supplies for the nurse or front office, and decorating bulletin boards. I’m sorry, this feels insane to me, and very much like the unpaid labor teachers already do, just usually from the comfort of their own home. None of the teachers I’ve spoken to seem to think this is out of line, and they all go every time. What do you think?

—Not Drinking That Kool-Aid

Dear N.D.T.K.A.,

OK, I hear you. And you’re not crazy. But I want to tell you this:

I love my Saturdays. I am very, very protective of teachers’ time. But I have worked for exactly three principals for whom I would do this exact thing for in a heartbeat if they asked me. For me, when I’m led by someone I respect and believe in, and when I can see for myself the vision they’re creating, I’m all in.

I would encourage you to try it out and see what you think. If it’s miserable, at least you tried. But what I can’t stop thinking about is that you haven’t found any teachers who complain about the community service thing. I’m thinking a school where the teachers don’t bat an eye about coming together to improve the school community is probably a pretty cool place to be.

That, or maybe a cult. Keep us posted.

Dear We Are Teachers,

I have a no-name “graveyard” in my 3rd grade class, a basket I’ve decorated with construction paper tombstones. When I get a worksheet that has no name on it, I put it in the graveyard and put a zero in the grade book as a placeholder. That notifies the parents their child has a missing grade, which prompts the student to look in the graveyard, put their name on it, and turn it in. This system has always worked for me … until last week. After report cards went out, parents basically started an uprising against my no-name policy and even the graveyard, citing it as too “macabre” for 3rd grade. My principal wants to meet next week. Should I be prepared to defend myself or eat crow?

—The Gravekeeper

Dear G.,

My first thought was that a graveyard isn’t too macabre for 3rd graders, but then again, as a child I pulled Thinner by Stephen King off my parents’ bookshelf and read it thinking it would be like Goosebumps, so maybe my expectations are a little askew. I do think that fun little tricks and traditions are part of what makes teaching so fun—and what makes teachers so memorable years later. Maybe the basket is decorated to resemble somewhere papers got lost rather than died. A corn maze? A labyrinth? Those circular clothing racks at Target?

Whatever you decide (and whatever your principal recommends), I do think a few things should be in place:

1. Parents should know about the no-name policy long before report cards.

The policy needs to be outlined in your syllabus or parent letter, and make sure to talk about it at open house. Frame it as one of the ways you help students become more responsible for their work in 3rd grade, and make sure parents know that as soon as the work is turned in, the grade will be updated.

2. Several days before report cards, meet with kids about their zeros and invite them to check if they’re in the no-name pile.

Also, send a mass email to all parents saying, “Hi parents! Grading deadlines are just around the corner. Today, I met with any students who are still missing work about getting those grades in. As a reminder, you can check the grade book yourself at https://www.weareteachers.com/behind-the-pacing-guide/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=behind-the-pacing-guide. Let me know if you have any questions.”

3. Compare the no-name pile against missing grades yourself.

Yes, even if you meet with kids and email parents, you will still have students who won’t check the no-name pile for their missing work. Ultimately, grades should be a reflection of students’ abilities in a given skill, not whether they remembered to write their name.

Finally, always be mindful about students with IEPs that might account for forgetfulness, overstimulation, impulsivity, or other factors that can make remembering to write your name genuinely tough (another reason it’s probably best to forego the graveyard imagery).

Do you have a burning question? Email us at askweareteachers@weareteachers.com.

Dear We Are Teachers,

Our principal recently announced that during parent-teacher conferences, we’re only allowed to share “positive feedback.” If there’s a concern—academic, behavioral, or otherwise—we’re supposed to keep it to ourselves and let the parents “enjoy a celebration of their child.” I get wanting to highlight strengths, but I also believe parents deserve an honest picture of how their kid is doing. What’s the point of a conference if I can’t address areas of growth? I feel like I’m being asked to sugarcoat reality, and it doesn’t sit right with me. How do I balance being truthful with respecting my principal’s directive?

—Positivity Prisoner