Moving Beyond Binary Thinking about Language in the Classroom

The concept of academic language is most widely attributed to Jim Cummins, who introduced the distinction between Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Cummins, 1979). BICS and CALP have been canon in ESL teacher education during the four decades that followed.

Amidst a global pandemic and the death of a black man under the knee of a white police officer, academic language was challenged by a new generation of scholars in 2020. A committee dedicated to Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice published the following demand, amongst others:

We DEMAND that teachers and researchers acknowledge that socially constructed terms such as academic language and standard English are false and entrenched in notions of white supremacy and whiteness that contribute to anti-Black linguistic racism (Baker-Bell et al., nd1).

That same year, Nelson Flores (2020) published “Are People Who Support the Concept of Academic Language Racist? An FAQ.” In it, he directly challenged Cummins’s conceptualization of BICS and CALP “When somebody describes children as having BICS but not CALP they are essentially arguing that they only engage in cognitively undemanding language practices… It also isn’t surprising that this framing would lead to remediation” (para. 3). As a field committed to social justice, educators have found themselves wedged between two seemingly polarized commitments about language in the classroom:

1. Educators acknowledge the importance of validating and valuing home languages and dialects and welcoming them into the classroom.

2. Educators acknowledge that academic English is a form of social capital, and it is our responsibility to provide students with this tool for social mobility.

Those who avert this binary and embrace both of these commitments maximize the growth potential of their students’ linguistic development. However, doing so requires sophisticated pedagogical skills. Our new book, Language of Identity, Language of Access (LILA): Liberatory Learning in Multilingual Classrooms, provides educators with a practical, teacher friendly guide to linguistically sustaining and expanding pedagogies that is rooted in the field’s leading theoretical foundations.

LILA offers a model for how to embrace this duality in the classroom. Practice informs theory, and theory informs practice in a complementary feedback loop. The concrete examples below are based in theory and can readily be implemented in your classroom. We call these Practical Applications of Theory or PATs.

The Language of Identity and Criticality

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings first published the theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in 1995. She asserts that instruction that supports culturally diverse students in school has three components: academic success, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. You can think of it as a dish with three main ingredients. These three ingredients must be present for the full plate.

Similarly, teaching linguistically diverse students calls for pedagogies that intentionally affirm who they are as multilingual individuals. The three components of the language of access, the language of identity, and the language of criticality align closely to the tenets of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. All are needed to support the learning of linguistically diverse scholars in schools.

The first ingredient of cultural competence presents as supporting the language of identity in the classroom. Dr. Ladson-Billings shared in an address at the University of Minnesota LEAD conference in July 2024 that “having cultural competence means knowing one’s culture deeply and at least another culture”. Fostering the language of identity therefore means designing learning experiences where students can develop a positive sense of self as multilingual learners. Consider using texts that can serve as both “windows and mirrors” for students regarding topics that touch on language communities. One text Natalia and her students loved was Code Talker by Joseph Bruchac. It provided a unique opportunity for students to learn an absent narrative of Navajo Peoples while also making connections to experiences about language. As a class community, we enjoyed responding to writing prompts that connected the book with our own experiences as a PAT. Students chose one of three prompts: 1) Write about a time you had to say goodbye to someone dear to you, 2) How is hair part of your identity? 3) Write about the story of your name. Students were provided guiding questions, graphic organizers, and other language supports to develop their writing (Benegas and Benjamin, 2024).

Using a text like the one mentioned above also provided a unique opportunity to develop the second ingredient: the language of criticality. Dr. Gholdy Muhammad (2020) shares that criticality is “critical thinking about power, justice, equity, humanity, problem solving, empowerment, marginalization, and types of criticality related topics” (p. 84). Reading a text like Code Talker created a unique opportunity to build the language of criticality in the classroom. In order to do so, students learned about Language Orientations (Ruiz, 1986) through visual notes (Benjamin and Benegas, p.152, 2024) to have a critical framework they could utilize to analyze how the Navajo language was perceived and the underlying power dynamics in the book’s societal context. The classroom PAT engaged students in critical analysis of the characters and the text and also made connections to their own experiences (Benegas and Benjamin, p. 160, 2024).

Other theoretical frameworks that support students’ development of the language of identity and the language of criticality are Translanguaging (Ofelia et. al, 2017), Community Cultural Wealth (Yosso, 2005), Raciolinguistics (Rosa and Flores, 2017), Historically Responsive Literacies (Muhammad, 2020), Critical Bilingual Literacy (España and Herrera, 2020) to name a few. LILA offers several PATs that can be used in classrooms so that students’ multilingual identities can be affirmed and students’ empowered for their own self-determination. The following section presents the third and final part of the dish, the language of access.

The Language of Access

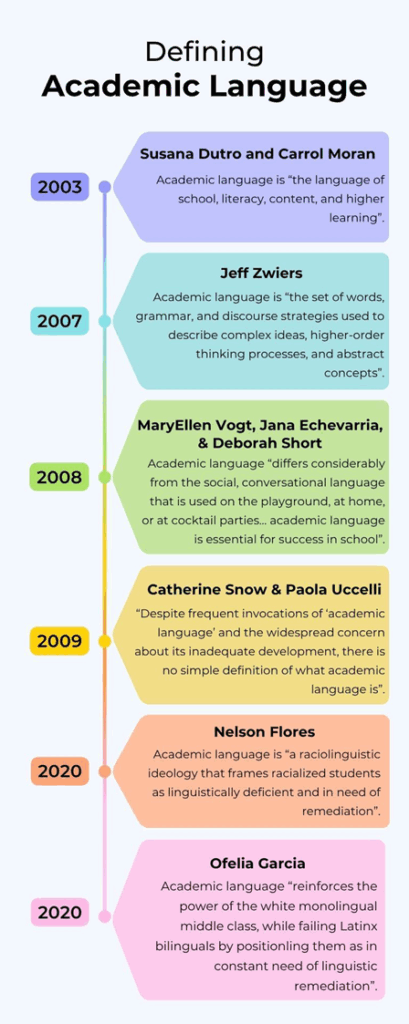

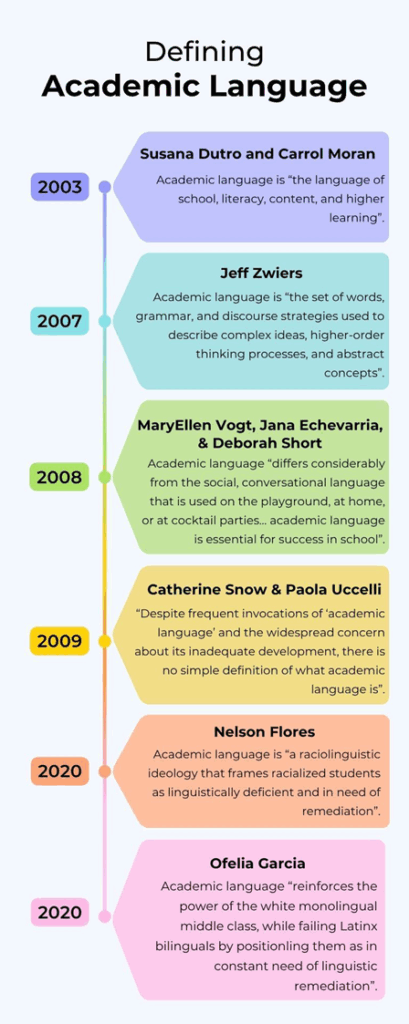

It is no surprise to those who study language that it is ever-changing. The reasons for replacing words vary and some linguistic shifts are felt more profoundly than others. Trace the evolving meaning of the term “academic language”, as described by leading scholars in the field.

For those of us who have centered our careers on the concept of academic language, this shift can feel uncomfortable. Our role as professionals is to listen to those who benefit from the term as well as those who are injured by it and draw our own conclusions. We have adopted the following stance:

At best, academic is an apolitical term that has taken on an exclusionary tone over time. At worst, it is a gatekeeping term referring to an academy that is entrenched in white supremacy and patriarchy. For this reason, instead of using the term academic language, this book refers to language that is outside of students’ existing language repertoire as the language of access. When it comes to the language of access, the role of teachers is to open as many doors as possible for students and to teach them how to open doors for themselves. (Benegas & Benjamin, 2024)

Let it be known that no rigor is removed with this shift in terminology! Teaching and learning language is as heavy a lift as it always was.

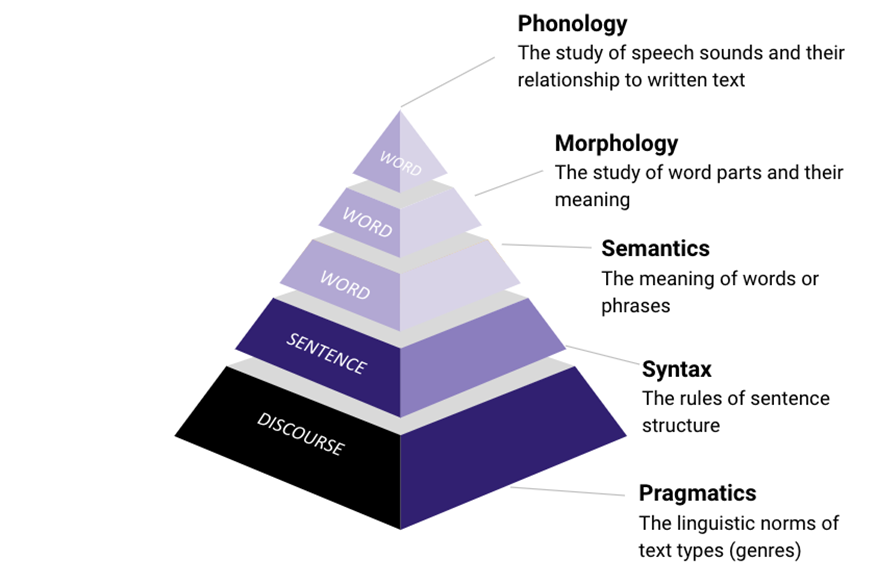

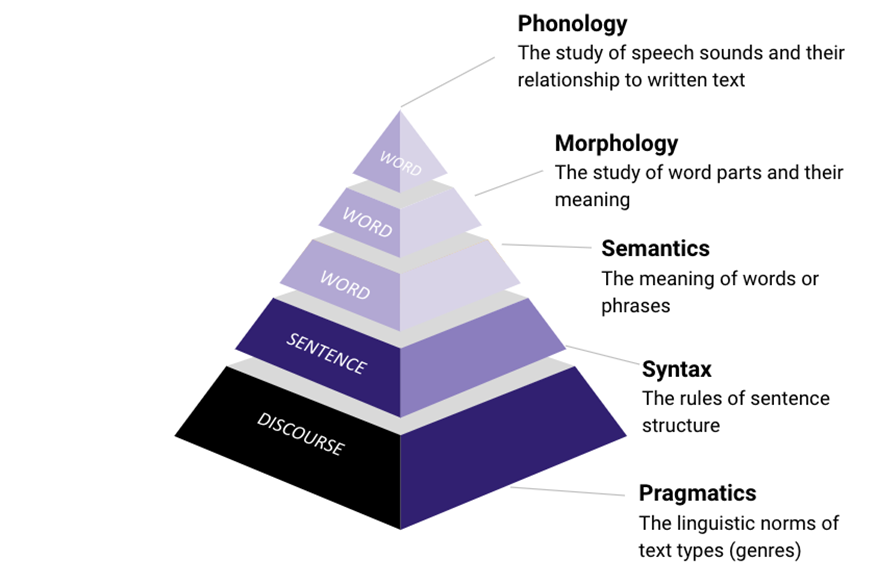

Contrary to the common saying, children are not “sponges”. They have complex minds and actively work to acquire new language. For this reason, explicit instruction in the language of access is paramount to educational equity for all learners throughout the school day and across subject areas. When it comes to attention to language, most educators focus on challenging, subject-specific vocabulary. However, word-level language is only one of three essential layers that students must engage with to fully engage with the curriculum.

A functionalist approach to language instruction asks educators to consider what specific language students will need in order to engage with the content. In doing so, they should consider the three levels of language and the corresponding five elements, from the smallest unit of language at the word level (the phoneme) to the largest at the discourse level (the genre). LILA offers PATs intended to expand students’ language across these three levels.

Educators can create language learning opportunities at all three levels of language through thoughtful planning. However, even when educators are onboard with leveling the linguistic playing field for multilingual learners through explicit language instruction, they may find it difficult to know which language to teach. The “noticing and forecasting” exercise is a guide toward making strategic instructional choices that promote linguistic equity for all students (Benegas & Stolpestad, 2025). See below:

| Approach to Planning for Language Instruction | Orientation | Prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Noticing | Reflective | What do I notice about my students’ language production that needs attention? |

| Forecasting | Forward-Thinking | What language do students need in order to engage in the lesson? |

Planning for LILA in the Classroom

When students are in need of developing foundational language skills, educators often default to exclusive, intense work on the language of access. And while it is true that some students need additional focus on the language of access, students are more apt to apply the language of access when it is practiced alongside the language of identity and the language of criticality. All three must be present and none should overshadow the other. Taking a personal inventory of our classroom practices as well as school-wide practices (Benegas and Benjamin, p. 298, 2024) can help us identify our areas of strength and growth in these three areas. With intentionality in our instruction, our students can develop their language skills while also enjoying a humanizing learning experience that affirms and empowers them.

Note

1 Since the list of demands was originally published in 2020, Baker-Bell et al. have changed the language of the first demand to “We demand that teachers stop using academic language and standard English as the accepted communicative norm, which reflects White mainstream English.”

References

Baker-Bell, A., Williams-Farrier, B.J., Jackson, D., Johnson, L., Kynnard, C., McMurty, T. (2020). CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice.

Benegas, M., Benjamin, N. (2024). Language of Identity, Language of Access (LILA): Liberatory Learning in the Multilingual Classroom, Corwin SAGE Press

Benegas, M., Stolpestad, A. (2025). Teacher Leadership for School-Wide English Learning (2nd ed), TESOL Press.

Cummins, J. (1979). Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic interdependence, the optimum age question and some other matters. Working Papers on Bilingualism, 19, 121–129.

Dutro, S.M., & Moran, C.E. (2003). Rethinking English Language Instruction: An Architectural Approach

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M. E., & Short, D. (2008). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP model (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson Allyn & Bacon.

España, C., & Herrera, L. Y. (2020). En Comunidad: Lessons for centering the voices and experiences of bilingual Latinx students. Heinemann Educational Books.

Flores, N. (2020). From academic language to language architecture: Challenging raciolinguistic ideologies in research and practice. Theory Into Practice, 59(1), 22–31.

Flores, N. (2020, February 1). Are people who support the concept of academic language racist? An FAQ [Blog post]. Educational Linguist. https://educationallinguist.wordpress.com/2020/02/01/are-people-who-support-the-concept-of-academic-language-racist-an-faq/

García, F., Solorza C. R. (2020): Academic language and the minoritization of U.S. bilingual Latinx students, Language and Education

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius. Scholastic Teaching Resources.

Rosa, J., & Flores, N. (2017). Unsettling race and language: Toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Language in Society, 46(5), 621–647. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404517000562

Ruíz, R. (1984). Orientations in language planning. NABE Journal, 8(2), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08855072.1984.10668464

Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P. (2009). The challenge of academic language. In D. R. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 112–133). Cambridge University Press

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1361332052000341006

Zwiers, J. (2007). Building academic language: Essential practices for content classrooms, grades 5–12. Jossey-Bass.

Michelle Benegas, Ph.D. (https://benegasconsulting.com/), is an associate professor at Hamline University and a co-founder of TESOL International Association’s School Wide English Learning (SWEL) Professional Development Series. Her books include Teacher Leadership for School-Wide English Learning and Language of Identity, Language of Access (LILA): Liberatory Learning in Multilingual Classrooms.

Natalia Benjamin was named the 2021 Minnesota Teacher of the Year and holds a National Board Teacher Certification. Her work focuses on multilingual education, identity work, Heritage Speakers, ethnic studies, language justice, and student-centered humanizing pedagogies. She co-authored: Language of Identity, Language of Access: Liberatory Learning for Multilingual Classrooms (Corwin, 2024).