New academic standards have drastically changed our expectations for student learning. However, most teachers have never experienced the type of learning called for in the World-Readiness Standards for Learning Languages (National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015). The present time provides a unique opportunity to change world language education for all students through enhanced views of teacher leadership.

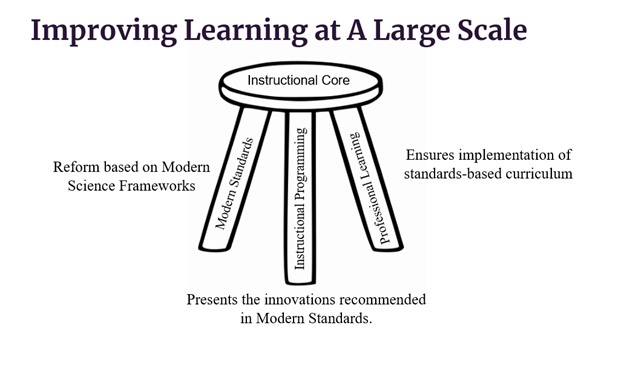

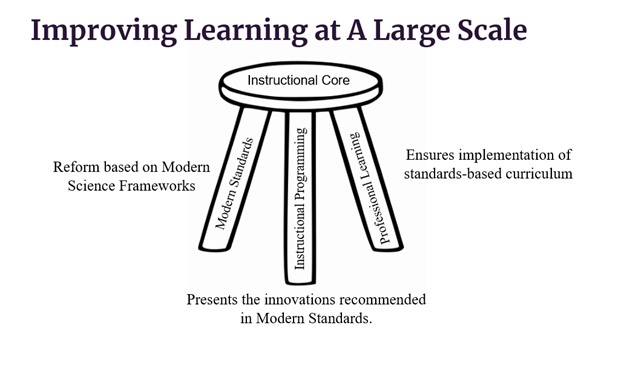

Richard Elmore (2009) proposes that to improve student learning on a large scale, we must focus teacher leadership on the instructional core. The instructional core includes three critical elements: (1) the need to reform based on modern frameworks for developing students’ local and global competencies and associated new state standards (ACTFL, 2012); (2) developing instructional programming, i.e., a curriculum, that presents the innovations recommended in the new state standards; and (3) providing the professional learning that teachers will need to effectively teach standards-based curriculum. These three instructional elements can be thought of as analogous to a three-legged stool—all three aspects are needed to provide a stable and strong ability to reach the vision of modern world language education.

Figure 1. Improving learning at a large scale

While this article is a standards-based reference, the standards are already set (Instructional Core Element 1). ACTFL’s construction calls for teachers to favor depth over breadth while engaging students in “using” world languages to communicate, not just learning vocabulary, verb conjugations, and scripted dialogues. These standards emphasize real communication and interaction in learning and not just knowing grammar rules and vocabulary. Though understanding standards and unpacking them in professional learning is a common activity, it often falls short of teachers developing deeper know-how and the “how to“ knowledge for putting modern reforms into practice (Wiggins and McTighe, 2012). Alas, as we all know from experience, what seems like a good idea—focusing professional learning on teaching educators about standards—has a common unintended consequence of teachers not developing the abilities to put the innovations required of standards into practice.

Ensuring the instructional core benefits all students calls for designing curriculum using research-based instructional models based on how students learn best (Instructional Core Element 2). We have successfully used an instructional sequence called explore-before-explain (see Brown and Richards, 2024) that provides world language teachers a prescribed instructional sequence of what to teach and when. The explore-before-explain sequence begins by targeting individuals’ lived experiences (Language 1 [L1]) and using them as assets to learning. This initial phase engages students’ inherent curiosity, invites their ideas, and sets the context for later learning related to the desired understanding. The most effective lessons are not just informational; they are experiences that deeply embed concepts, fostering long-lasting understanding. Sensemaking is key to a learner-centered environment and centers around language features that invoke questions and relate to students’ lives. Next, students’ ideas should lead directly to minds-on experiences and promote critical and logical thinking that provides evidence for developing understanding. In knowledge-centered classrooms, students should know how ideas connect and how they equip them with valuable skills. As students work to construct a more robust understanding, they inherently integrate L1 and new language learning.

Tables 1 a, b, c. Strategies to engage French, German, and Spanish teachers’ prior knowledge and use critical thinking to promote active meaning making.

| French | English |

| Monb oncle a est pilote a. | Myb uncle a is ac pilot a. |

| Mab mère est pilote a. | Myb mother a is ac pilot a. |

| Monb père est mécanicien a. | Myb father a is ac mechanic a. |

| Ma cousine est mécanicienne.a,b. | Myb female cousin a is ac mechanic a,b. |

| Patterns and Causal Relationships, French-English | |

| 0. Both written and spoken language developed from prior ideas and experiences (recognizable cognates) a. Gender-specific spelling and words b. Using “a” in English sentence construction is understood |

|

| German | English |

| Meinb Vatera,b,c ist Mechanikera,b,c. | Mybfathera,b,c is ad mechanica,b,c. |

| Meinb Onkela,b,c ist Pilota,b,c. | Myb unclea,b,c is ad pilota,b,c. |

| Meineb Muttera,b,c ist Pilotina,b,c. | Myb mothera,b,c is ad pilota,b,c. |

| Meineb Cousinea,b,c ist Mechanikerina,b,c. | Myb female cousina,b,c is ad mechanica,b,c. |

| Patterns and Causal Relationships, German-English | |

| 0. Both written and spoken language developed from prior ideas and experiences (recognizable cognates) a. Gender-specific spelling and words b. Capitalization of nouns c. Using “a” in English sentence construction is understood |

|

| Spanish | English |

| Mi tío es pilotoa. | My uncle is ab pilota. |

| Mi madrea es pilotoa. | My mothera is ab pilota. |

| Mi padrea es mecánicoa,b. | My fathera is ab mechanica,b. |

| Mi prima a es mecánicaa,b. | My female cousin a is ab mechanic a,b. |

| Patterns and Causal Relationships, Spanish-English | |

| 0. Both written and spoken language developed from prior ideas and experiences (recognizable cognates) a. Gender-specific spelling and words b. Using “a” in English sentence construction is understood |

|

The importance of explore-before-explain underscores a critical point in the scholarship: If you are in a district where level one world language learning does not occur until ninth grade, the culminating impact of explore-before-explain is significant and exceeds how much programs can grow students’ proficiency over time. Large-scale meta-analyses show that explore-before explain experiences influence student achievement, conceptual understanding, motivation, and engagement compared to traditional approaches (Bybee et al., 2006). These approaches do not just nudge the needle; they propel students forward with such a dynamic force that some soar months ahead of their peers in traditional classroom atmospheres (Austin et al., 2023). Thus, these planning considerations align perfectly with research that advocates for language educators to facilitate learning rather than dispense knowledge, and to expose students to comprehensible language through the conceptual lenses of speaking, writing, listening, and reading rather than focusing on memorization and rote knowledge (ACTFL, 2012; Krashen, 2003; National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015; Werbinska, 2009). Moreover, it has become important to recognize in our digital world (i.e., AI) that we can no longer view educators as just knowledge dispensers.

Curriculum-Based Professional Learning

High-quality professional learning is about creating an experience that is as engaging as it is enlightening. Whether implementing a commercially developed program or a district created curriculum, teacher leaders should have in-depth experiences with high-quality professional learning (Instructional Core Element 3). Leaders can look to the well-established research base on the characteristics of effective curriculum based professional learning, which emphasizes the following key features (Linda Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Short and Hirsh, 2023):

• Content-focused and standards-aligned: Deepens educators’ understanding of what to teach and how to teach it within the context of the standards, local curriculum, and high-quality instructional resources.

• Equity-focused: Empowers educators to captivate every student, tailoring engaging tasks to diverse needs and abilities.

• Considerate of adult learners: Addresses expressed and unexpressed expectations and motivations while attending to mindsets; builds on participants’ prior knowledge and experience and invites them to connect learning to meaningful goals and immediate valuable actions.

• Learner-centric: Inquiry-based, interactive, and collaborative. Involves expert models and practice as educators participate in lessons as learners, plan, internalize, rehearse, observe, and reflect with colleagues who teach in the same content area and use the same curriculum.

• Provides coaching and expert support: Offers expertise about curriculum, adopted high-quality instructional resources, and evidence-based practices, focused directly on educators’ and students’ individual needs.

• Offers feedback and reflection: Provides job-embedded time for educators to think intentionally, receive input, and refine practice. Educators need adequate time to learn, rehearse, implement, and reflect upon new strategies that facilitate refinements in practice over time.

Leaders might wonder how to incorporate the essential elements of effective professional learning to promote the same critical thinking for teachers that contemporary world language standards require of students (Short and Hirsh, 2002). In that case, they might use a single model lesson and teachers as proxies for students to engage them in active meaning-making for the innovations desired (ACTFL, 2012).

Table 2. French, German, and Spanish transfer activities that promote and visible learning

| German | Spanish | French | English |

| Steve ist athletisch. Steve spielt Basketball! Steve spielt gut Basketball! Steve spielt Basketball besser als Lebron James! | Steve es un atleta. Steve juega baloncesto. ¡Steve juega bien al baloncesto! Steve juega al baloncesto mejor que Lebron James. | Steve est athlète. Steve joue au basket. Steve joue bien au basket ! Steve joue mieux au basket que Lebron James. |

Steve is an athlete. Steve plays basketball. Steve plays basketball well! Steve plays basketball better than Lebron James. |

Strategies for Engaging Teachers in Meaningful Professional Learning

Leaders can engage teachers in meaningful inquiry by using content-specific examples to drive learning that could occur in a typical day in a standards-minded level-one world language classroom. Teacher leaders of and within departments that include French, German, and Spanish can engage their teachers by activating their prior knowledge to promote deeper learning in the same way that students’ ideas are engaged. We advocate that teachers try the following activities during professional learning for three critical reasons:

1. They embrace the intellectual power in how new language learning can flourish from prior knowledge (L1). Language comparisons such as these help students compare their L1 with the new language being studied (ACTFL, 2012);

2. They help teachers understand the implications of emphasizing critical thinking in new language learning through pattern recognition and cause–effect relationships. Promoting critical and logical thinking helps transition from novice to intermediate levels of world language proficiency (Swender et al., 2012) and is key to the ACTFL learning targets (ACTFL 2012); and

3. In sum, modern learning theory advocates for blending critical-thinking skills with new content learning as central organizers for helping students construct knowledge of discipline-specific content (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2010).

While students’ developing frameworks for organizing new knowledge are essential, they are not always sufficient to ensure deep conceptual understanding of and desired proficiencies in standards, nor do they help teachers decide where to go next during instruction. Teachers can help students better understand the differences between L1 and new languages and cultivate a more sophisticated and enhanced understanding (e.g., when applicable, explain important grammatical and sentence structures). Enhancement activities must be time- and experience-sensitive and should answer why and how questions, especially ones that students generate in their attempts to make meaning, and help them transfer their learning to new situations. This view aligns with the recommendation of curriculum experts that educators move away from trying to cover volumes of factual material and instead prioritize their curriculum around a smaller number of conceptually more critical, transferable ideas (e.g., Wiggins and McTighe, 2011). Teachers can get a feel for how to test their abilities to transfer ideas to new and more complex situations similar to the ways we want students to in world language classrooms. Through a combination of enhancement activities (transfer practice and promoting visible learning), teachers can rank their confidence in their abilities using a simple three-point scale: (1) I know what all of the words mean in the sentence; (2) I know what some of the words mean in the sentence; and (3) I do not understand the sentences or paragraph. Thus, the evaluation aims to promote reflection and assessment of the developing sensemaking of new languages that aligns with ACTFL’s ideas about proficiency grading (e.g., 1. not yet proficient; 2. functionally proficient; 3. fully proficient) (ACTFL 2012).

Take Action

The crucial components of effective professional learning and the strategies provided to engage teachers in developing deep conceptual understanding must be done regularly and obsessively in our schools and district training and PLCs (professional learning communities), as well as in graduate and undergraduate coursework. If we do these things, we can expect to profoundly impact how we think about student motivation, learning, and achievement by building teachers’ collective efficacy through more purposeful teacher leadership (Hattie, 2023). The ideas from high-quality professional learning must be translated into teachers’ firsthand practice with students. Leaders should promote teacher teams using the lesson with classes while reflecting on student learning during each phase of instruction. In addition, participating in co-teaching and peer observations of the lesson, receiving colleague feedback, helps make the connections between learning and research even more concrete. Leaders can highlight that we can expect more than incremental changes by zeroing in on the features of high-quality instructional design. In fact, the practice of providing effective curriculum-based professional learning that is tested firsthand with students offers what Michael Fullan calls “stunningly powerful consequences” for students and teachers alike.

Conclusions

Modern standards create a golden opportunity to enhance student achievement nationwide. However, it is more complex than adopting modern standards and nudging teachers toward instructional shifts—it requires an enhanced view of world language education leadership. The real magic happens when we dive deep into the heart of our classroom practices and the activities students have daily, where the instructional core resides.

References available at https://languagemagazine.com/references-leadership-july-2025/

Patrick Brown is executive director of STEAM for the Fort Zumwalt School District in O’Fallon, Missouri, and author of the bestselling National Science Teaching Association book series Instructional Sequence Matters.

Eric Richards is an experienced and recognized world language educator. He is also a presenter, author, trainer, speaker, and curriculum specialist. He is the author of a series of CI/ADI-based readers and other books and materials for students and educators in the world language classroom.