As the Science of Reading (SoR) gains traction across states, schools, and teacher preparation programs, a pressing question has emerged: How well does the SoR framework serve multilingual learners (MLs)? The Reading League (2021, para. 1) defines the SoR as “a vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing,” drawing from fields such as cognitive psychology, linguistics, neuroscience, and education. Proponents champion its research-based foundations and its potential to improve reading outcomes through explicit, systematic instruction. For many educators, the SoR has provided much-needed clarity, structure, and a corrective to years of inconsistent literacy practices. Success stories—such as the widely cited Mississippi Miracle—offer compelling evidence of its impact (PBS NewsHour, 2023).

At the same time, concerns have grown that common interpretations of the SoR overlook the linguistic and cultural realities of multilingual learners (MLs). Many policies lean on monolingual norms, missing the distinct needs of MLs acquiring literacy in another language. The friction, however, often stems not from the research itself but from how it is translated into practice—frequently through deficit-based assumptions about multilingualism. MLs have long been viewed through a remedial lens, rather than recognized for the linguistic and cultural resources they bring. Encouragingly, a growing number of initiatives—such as the READ Act Reauthorization of 2023, the Golden State Literacy Plan (2025), and Colorado’s Dyslexia Screening and READ Act Requirements—mark a shift toward more inclusive literacy policy.

We write to district leaders, classroom educators, researchers, and policymakers alike—because advancing equity in literacy requires a shared responsibility. Together, we represent K–12 educators, district leaders, and higher education faculty, each with extensive experience supporting MLs in varied educational contexts. The tensions explored in this article draw from each of our perspectives, and the solutions are both structural and instructional.

This article moves beyond binary views that separate the SoR from ML instruction. We examine where the SoR aligns with ML needs, where it requires thoughtful adaptation, and how literacy instruction can better reflect the cultural and linguistic diversity of today’s classrooms. We identify persistent misunderstandings, highlight key tensions, and offer research-informed solutions for a more equitable literacy future. We begin with a critical examination of the SoR evidence base itself—asking: Who was included in the research, and what can ML programs gain from it?

Widespread Assumption: The Science of Reading Research Fully Represents All Learners

The SoR is often presented as a settled body of knowledge. Yet its empirical base largely stems from research on monolingual, English-speaking children. This presents a critical tension: MLs—a growing segment of US students—are underrepresented in the foundational studies shaping SoR-aligned policy and practice. Influential research frequently cited in SoR literature, such as the National Reading Panel’s Teaching Children to Read (2000) and Shaywitz’s Connecticut Longitudinal Studies (1990 onward), offers limited attention to MLs and fails to clarify the narrow generalizability of their findings. Framing these studies as universally applicable perpetuates a myth of inclusivity that overlooks the realities of today’s classrooms.

Why is this point of tension important?

This omission is not merely academic—it carries real classroom consequences. Frameworks and assessments designed for monolinguals, when applied without adaptation, risk misinterpreting MLs’ strengths. For example, while phonological awareness and decoding are key SoR components, their development may follow different trajectories for MLs. Students may demonstrate literacy skills in their home language(s) or use cross-linguistic strategies that do not align with English-only performance benchmarks. Without understanding how cross-linguistic transfer or varied exposure shape learning, educators may mistake differences for deficits.

Shining a Light

A growing body of research in applied linguistics and bilingual education offers key insights. Scholars such as Geva and Siegel (2000) and Koda (2007) show that phonological and literacy skills can transfer across languages, depending on linguistic and orthographic distance. García (2009) argues that translanguaging is a strategic tool, not an obstacle to learning. Though much of this work is qualitative or literature-based, it remains foundational. Syntheses like “Developing Literacy in Second Language Learners” (August and Shanahan, 2006; 2023) affirm that while core reading components matter, they are not sufficient. The Council of the Great City Schools’ Framework for Foundational Literacy Skills Instruction for ELs (2023) calls for more large-scale, longitudinal, and mixed-method studies that focus specifically on MLs. Oral language, sociocultural context, and learner variation must also be addressed.

The Call to Action

- The research base must evolve. We urge researchers, policymakers, and educators to:

- Conduct large-scale, interdisciplinary studies that center MLs and reflect classroom diversity;

- Integrate research linking reading components with oral language, sociocultural context, and cross-linguistic transfer;

- Ensure MLs receive literacy instruction grounded in the five core components of reading—delivered in ways that honor their full linguistic repertoires.

Point of Tension: Science of Reading Reforms Can Overlook the Foundations of ML Instruction

This disconnect between research and real classrooms is further compounded by how SoR reforms are translated into policy and practice—often overlooking foundational principles of ML instruction. Across districts, ML teachers are evaluating how new literacy reforms align with—or inadvertently undermine—core principles of language development. Concerns have emerged around one-size-fits-all models that neglect the unique needs of MLs, narrowing learning experiences and sidelining asset-based approaches. Also troubling is the underrepresentation of ML teachers’ expertise in SoR-aligned decision-making.

This points to a necessary conversation—not about whether SoR and ML instructional approaches are compatible, but how they can be aligned meaningfully. MLs deserve equitable, evidence-aligned literacy instruction. Yet problems arise when rigid mandates overlook linguistic diversity. Often, the tension stems less from SoR itself and more from gaps between theory, professional development, curriculum, and practice—especially around ML instruction.

Why is this point of tension important?

Skepticism around SoR is often rooted in two issues: how it is operationalized and how it may marginalize MLs and their teachers. In many schools, SoR is introduced narrowly—centered on foundational skills like phonics and decoding—while underemphasizing oral language, comprehension, and culturally responsive pedagogy. This can leave educators torn between mandates and students’ needs—particularly when ML standards are overlooked and the expertise of ML teachers is underutilized.

Shining a Light

This challenge points to an opportunity. While educators are essential to instruction, they are often excluded from planning. When SoR is understood not as a phonics-only script but as a broad, research-based framework, it can align with ML priorities. This requires inclusive leadership and protected time for teacher collaboration.

The Call to Action

We call for deeper alignment between SoR and ML instruction by:

- Recognizing ML instruction as its own discipline with unique standards;

- Valuing ML teachers in literacy planning;

- Widening the SoR lens in support of inclusive, asset-based practices.

Common Concern: Language Comprehension Is Underemphasized in SoR Implementation

As SoR-aligned practices are implemented, ELA classes may see an increased emphasis on word recognition, leaving educators wondering if SoR meets the language needs of MLs. Growing concern has emerged that current interpretations of the SoR give disproportionate attention to foundational skills—such as phonics and phonemic awareness—while underemphasizing language comprehension. This imbalance is especially consequential for MLs, for whom oral language development, background knowledge, and academic vocabulary are critical to reading success.

Why is this point of tension important?

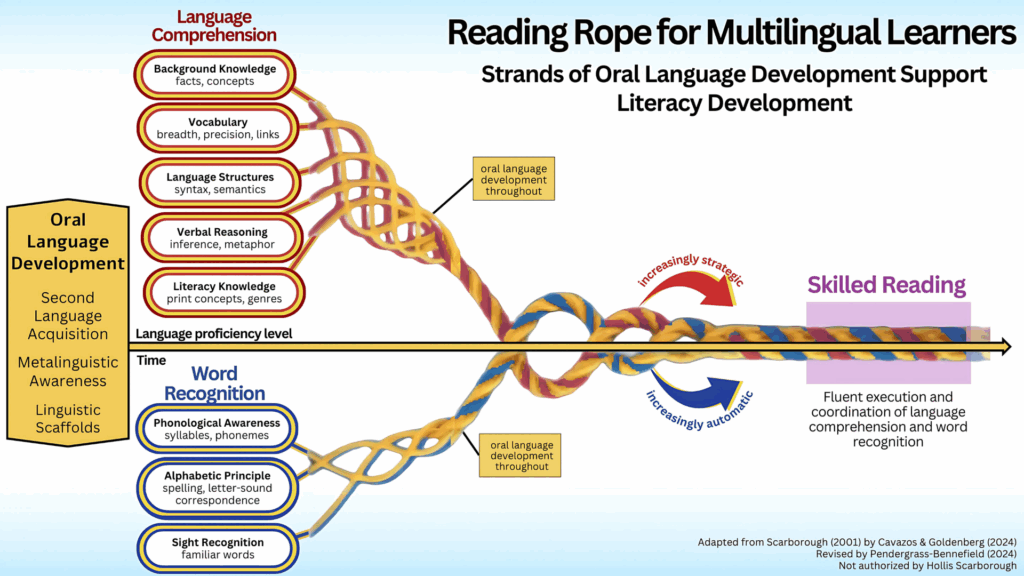

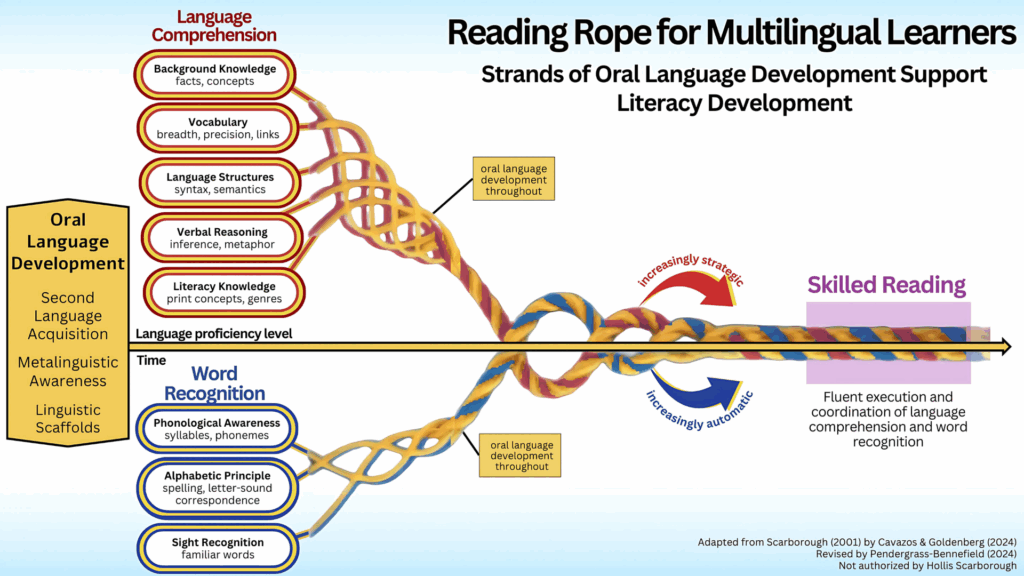

Districts often adopt scripted curricula prioritizing foundational skills to ensure equitable Tier 1 instruction. While some offer supplemental strategies for MLs, few center on their unique needs. Meanwhile, ML instructional standards often omit explicit foundational skills. While phonological awareness and decoding are vital, they must not eclipse broader dimensions of Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001)—such as vocabulary and background knowledge.

Shining a Light

Phonics is essential—but it is only one of the five foundational pillars identified in SoR. When initiatives narrow SoR to phonics alone—especially via scripted programs—they marginalize strategies critical for ML success. August and Shanahan (2023) underscore this in their review: “It is not enough to teach language-minority students reading skills alone. Extensive oral English development must be incorporated into successful literacy instruction” (p. 10).

Foundational models—Chall’s (1996) stages of reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001)—emphasize that decoding is only one part of skilled reading. Cavazos and Goldenberg’s (2024) model (see below) highlights how oral language supports all components of the rope.

Thus, SoR-aligned instruction must integrate both word recognition and language comprehension. A complete vision of literacy makes space for both code- and meaning-focused approaches to work in tandem.

The Call to Action

To better serve MLs, we urge educators to:

- Build background knowledge and vocabulary through relevant texts tied to students’ experiences and languages;

- Align vocabulary with unit themes across languages;

- Integrate cross-linguistic phonemic awareness to support both decoding and comprehension.

Point of Tension: The Role of Home Language in SoR-Aligned Instruction Is Often Overlooked

Language comprehension is essential—but how is home language valued in SoR? While SoR promotes evidence-based reading practices, its dominant research base and implementation plans have often developed without adequately considering MLs or the linguistic assets they bring—especially their home languages. As a result, many educators express concern that home languages are not only undervalued but actively excluded from SoR-aligned reading frameworks.

Why is this point of tension important?

Although federal documents—such as those from the Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA, 2025)—affirm the value of students’ home languages, this recognition is often absent from state legislation and curricular guidance. This omission raises significant concerns around equity and linguistic justice. Many general education and ML specialists lack preparation in how to integrate home languages to support cross-linguistic transfer. The limited research base disaggregated for MLs further compounds the challenge (Noguerón-Liu, 2020), leaving few models for incorporating home language use into SoR-aligned instruction.

Shining a Light

Despite these concerns, there is a growing recognition of the role home languages play in literacy development. A 2023 joint statement by The Reading League and the National Committee for Effective Literacy describes MLs’ home languages as “an asset that should be valued and nurtured… [to] leverage second language acquisition and second language literacy development” (p. 6). Instructional practices that help students connect their home languages and English are explicitly encouraged (The Reading League, 2023).

The Call to Action

To build a more inclusive vision of evidence-based literacy, we must:

- Use language transfer charts to support cross-linguistic connections;

- Create structured opportunities for home language use;

- Learn about students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds to inform instruction.

Persistent Assumption: Foundational Reading Instruction Falls Outside the Scope of ML Teaching

These instructional gaps raise important questions about roles: If classroom teachers focus on foundational skills, what is the role of ML educators in this landscape? Some educators view the call for ML programs to teach foundational reading skills—like phonics and decoding—as outside of the scope of their role. Dr. Tim Boals, co-founder of WIDA, clarifies that ACCESS for ELLs “does not measure multilingual learners’ reading skills in the content area of language arts, but rather their language proficiency to engage with reading materials across all content areas” (Boals, 2024, para. 4). This has led some to believe ML teachers should focus solely on language access, not foundational reading instruction. But how does that play out in practice?

Why is this point of tension important?

In the early grades, classroom teachers often handle phonics while ML teachers support comprehension. But by third grade and beyond, if ML instruction continues to emphasize only language comprehension, who addresses the persistent foundational needs of MLs—especially when these skills remain essential for learning and testing?

Shining a Light

Shared responsibility is both necessary and possible. The Georgia Department of Education (2024) affirms that “the responsibility for educating the whole English learner…is shared by regular classroom teachers and English language specialist teachers alike” (p. 4). Similarly, Maryland’s largest district states, “ESOL teachers must now prepare students not only for communicative competence but academic competence as well” (Montgomery County Public Schools, 2024, p. 2).

The Call to Action

To align with shifting expectations, we must reposition ML educators as integral to foundational literacy instruction. We urge educators to:

- Reflect on how reading proficiency is assessed and supported for MLs;

- Equip ML teachers to address foundational skills;

- Reframe the question from “Why must we change?” to “Who benefits if we do?”

Structural Tension: One-Size-Fits-All SoR Implementation Can Conflict with Dual Language Goals

These questions become even more complex in dual language settings, where the goal is not just English literacy—but biliteracy and bilingualism. Critics of current SoR implementation argue that its framework—grounded largely in monolingual research and English-dominant contexts—can unintentionally undermine the goals of dual language (DL) programs. The core tension stems from a mismatch in purpose: SoR is often applied through an English-only lens, while DL programs aim to cultivate biliteracy, bilingualism, and biculturalism.

Why is this point of tension important?

Many SoR-aligned materials and professional development efforts offer minimal guidance for bilingual or dual language settings. The dominance of English-only assessments, limited materials in partner languages, and lack of culturally responsive practices pose challenges (García & Kleifgen, 2018). In practice, rigid SoR models can reduce instructional time in the partner language, threatening students’ opportunities to develop biliteracy and linguistic equity.

Shining a Light

The solution is not to reject structured literacy but to expand it through a multilingual lens.

Systematic, explicit instruction should honor the linguistic features, orthographic systems, and developmental pathways unique to each language. Effective biliteracy instruction recognizes cross-linguistic transfer and cognitive interplay. As Johnson, García, and Seltzer (2019) affirm, translanguaging pedagogies and biliteracy frameworks can successfully coexist with evidence-based instruction–when both are grounded in high expectations, linguistic equity, and intentional design.

The Call to Action

To ensure SoR supports rather than hinders DLI/bilingual education, we urge districts and policymakers to:

- Invest in authentic, culturally responsive, and linguistically appropriate materials—not direct translations of English content (Grosjean, 2010);

- Develop coordinated biliteracy frameworksthat align scope, sequence, and themes across languages (Beeman & Urow, 2013);

- Design assessment and accountability systems that center biliteracy outcomes—not just English proficiency(Johnson, García, & Seltzer, 2019).

To move the language education field forward and avoid the risk of stagnation, the points of tension outlined here must be acknowledged and addressed directly. There is power in moving beyond polarizing catchphrases and oversimplified narratives—common on all sides of the conversation—and instead, engaging in collaborative, evidence-informed inquiry grounded in the lived realities of MLs and those who teach them.

We write to educators, researchers, district leaders, and policymakers alike because advancing equity in literacy requires shared responsibility. As part of that effort, we invite you to explore SoR with MLs, a resource hub created by the authors (accessible via the link and/or QR code below). This site is our collective offering to the field—a curated resource to help educators bridge multilingual practices with SoR principles.

Resource Hub for Effective Implementation of SoR with MLs

References

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (2023). Response to a review and update on Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language Minority Children and Youth. Reading Research Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.516

Beeman, K., & Urow, C. (2013). Teaching for biliteracy: Strengthening bridges between languages. Caslon Publishing.

Boals, T. (2024, October 15). WIDA response. Language Magazine. https://languagemagazine.com/2024/10/15/wida-response/

California Governor’s Office. (2025, June 5). The Golden State Literacy Plan [PDF]. https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/The-Golden-State-Literacy-Plan.pdf

Cavazos, L., & Goldenberg, C. (2024, June 10). The science of teaching reading for multilingual learners. [Professional learning workshop]. Floyd County District Office, Rome, Georgia.

Chall, J. S. (1996). Stages of reading development (2nd ed.). Harcourt Brace.

Colorado General Assembly. (2025). SB 25‑200: Dyslexia Screening and READ Act Requirements [Legislative bill]. Legislative Council Staff. https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb25-200

Council of the Great City Schools. (2023). A framework for foundational literacy skills instruction for English learners: Instructional practice and materials considerations. https://www.cgcs.org/cms/lib/DC00001581/Centricity/domain/35/publication%20docs/CGCS_Foundational%20Literacy%20Skills_Pub_v11.pdf.

García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley-Blackwell.

García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2018). Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs, and Practices for English Learners (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Georgia Department of Education. (2024, September). A resource guide to support school districts’ English learner language programs. https://url.gadoe.org/zfvi0

Grosjean, F. (2010). Bilingual: Life and reality. Harvard University Press.

Geva, E., & Siegel, L. S. (2000). Orthographic and cognitive factors in the concurrent development of basic reading skills in two languages. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12(1-2), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008017710115

Johnson, S. I., García, O., & Seltzer, K. (2019). Los Círculos: Redesigning literacy assessment through translanguaging. CUNY-NYSIEB. https://ofeliagarciadotorg.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/johnson-garcia-seltzer-2019.pdf

Koda, K. (2007). Reading and language learning: Crosslinguistic constraints on second language reading development. Language Learning, 57(s1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.101997010-i1

Montgomery County Public Schools. (2024). The role of the ESOL teacher. https://www.montgomeryschoolsmd.org/siteassets/district/curriculum/esol/cpd/module1/docs/roleesolteachertext.pdf

National Reading Panel. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Noguerón‐Liu, S. (2020). Expanding the knowledge base in literacy instruction and assessment: Biliteracy and translanguaging perspectives from families, communities, and classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.354

PBS NewsHour. (2023, September 7). Kids’ reading scores have soared in Mississippi “miracle”. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/kids-reading-scores-have-soared-in-mississippi-miracle

READ Act Reauthorization Act of 2023, H.R. 681, 118th Cong. (2023). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/681

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 1, pp. 97–110). Guilford Press.

Shaywitz, S. E., Shaywitz, B. A., Fletcher, J. M., & Escobar, M. D. (1990). Prevalence of reading disability in boys and girls: Results of the Connecticut Longitudinal Study. JAMA, 264(8), 998-1002.

The Reading League. (2021). Science of reading: Defining guide. https://www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the-science-of-reading/

The Reading League, & National Committee for Effective Literacy. (2023). Understanding the difference: The science of reading and implementation for English learners/emergent bilinguals (ELs/EBs) [Joint statement]. The Reading League. https://www.thereadingleague.org/compass/english-learners-emergent-bilinguals-and-the-science-of-reading/joint-statement/

U.S. Department of Education, Office of English Language Acquisition. (2025). Implementing evidence-based instructional practices for English learners: Using research to guide practice. U.S. Department of Education. https://ncela.ed.gov/sites/default/files/2025-01/oelaevidencepracticebrief-01132025-508.pdf

Dr. Jennifer Pendergrass-Bennefield is coordinator of ESOL, Title III, and literacy legislation, Floyd County Schools, Georgia.

Dr. David L. Chiesa is clinical assistant professor, the University of Georgia, Language and Literacy Department.

Dr. Rebecca Raab is assistant professor and Elementary Education Program chair, Columbia College, South Carolina.

Rachel Hawthorne is senior multilingual literacy specialist, Really Great Reading.

Susan Mann is literacy coach, Rome City Schools, Georgia.

Dr. Margaret McKenzie is director of multilingual programs and services, Atlanta Public Schools, Georgia.

Courtney Morgan is assistant professor of teacher education/director of Elementary Education Program, Brevard College, North Carolina.

Kristin Rush is ELA interventionist, Floyd County Schools, Georgia.