Challenges English Learners Face Engaging in Lesson Tasks

As an experienced instructional coach, a persistent challenge I observe for K–12 English learners is simply understanding what they are supposed to do and why. To fully engage in a lesson, whether within a dedicated ELD context or core content class, students in early stages of English proficiency need the teacher to meticulously set up every task. Across the school day, emergent bilinguals are routinely expected to participate in standards-aligned tasks alongside more proficient English peers. Unfortunately, veteran and neophyte teachers alike may operate with insufficient strategic know-how to ensure their students newly acquiring English can confidently approach a lesson task.

Multilingual learners are not apt to get off to a promising start on either an independent or a collaborative task if they do not comprehend the content, vocabulary, and procedural expectations. Hasty or extemporaneous verbal directions without visual aids perplex second-language listeners and tax their short-term memory. When students are also expected to begin identifying text evidence or sharing their mathematical thinking without effective teacher modeling, the odds are slim that an English learner will experience any time on task.

To ensure emergent bilinguals approach a lesson task with clarity and confidence, teachers must conscientiously display, read, and unpack directions. This includes carefully demonstrating the required steps and providing accessible models of desired work. Of equal importance, our multilingual scholars benefit from understanding the purpose of the task so they perceive the importance of what they are doing and how it will advance their English language skills and subject-matter knowledge.

Ensure a More Productive Start on Lesson Tasks

Because effective task setup for multilingual learners is such an endemic instructional challenge, my associates and I make this a priority when preparing instructional resource specialists, classroom teachers, and administrators alike. Whether supporting English learners in a pull-out, co-teaching, or dedicated ELD context, K–12 educators must make every effort to get all students off to a confident start on focal lesson tasks. The following step-by step process is gleaned from a decade of dedicated and integrated ELD-focused research projects, professional development, and technical coaching across grade levels (HMH, 2025; Kinsella, 2018). While to some it may appear overly detailed, this is the level of instructional precision warranted when serving students who are dually identified or entering and emerging English learners.

A Close Look: Setting Up a Lesson Task (Adapted from Kinsella, 2024b)

1. Clearly display lesson content.

• Project content (e.g., lesson page, directions, discussion prompt) that is large enough for every student to easily see.

• Position yourself so you can gesture to the specific lesson content you are focusing on.

• Ensure the projected content is adequately enlarged and aligned, not skewed.

• Use a bold and bright color to heighten visibility when offering a model response with a language scaffold such as a response frame.

2. Direct students’ attention.

• Call students’ attention to the board, screen, lesson page, or visual using clear and consistent wording: Let’s look at…; Now, let’s focus on…; Let’s move to our practice task.

• Make sure students are looking at the right content and demonstrating with a physical evidence check. Cue students to point, circle, highlight or place a guide card beneath the focal lesson content. Provide students with a colored cardstock bookmark to help them navigate a lesson page and signal to you that they are in the right place. Place your blue guide card under the discussion prompt. Now, let’s read the prompt together to make sure we all understand what to do.

• When the class includes students who need extra support, such as newcomers or dually identified learners, cue assigned partners to check whether theirs are on the right page, pointing to the correct problem, etc. Check to make sure your partner is pointing to the first section heading as I am. Pencils up if you and your partner are both ready to read.

3. Establish the purpose of the lesson task.

• At the beginning of the lesson, state the overarching lesson purpose, making connections to the previous day’s learning. For each micro-task within a lesson, provide a brief, accessible purpose: Now that we have read this text section twice, we are ready to mark important details.

4. Introduce the lesson task.

• Briefly and clearly describe what students are going to do. You are going to reread this text section and find three important details about common breakfast foods.

5. Guide fluent reading of task directions: tracked and echo reading. (See Kinsella, 2024b, for detailed guidance on instructional routines for building reading fluency.)

• Direct students’ attention to the directions. Point to the blue box, like me. Put down your pencil and look at our partner discussion task on the board.

• Guide fluent reading of the directions with an initial tracked read. Let’s read the directions to under stand what we need to do. Follow along with your eyes and (finger, pencil, cursor, guide card) while I read aloud.

• Guide fluent rereading of the directions with phrase-cued echo reading: I’ll read and you echo back. Identify and highlight… three important details… that support the key idea. Discuss important details… with your lesson partner… using the sentence starters.

6. Explain the task, model the steps, and demonstrate required skills.

• Explain the task briefly. First, you will find and highlight important details in the text. Next, you will discuss these details with your partner using a sentence starter.

• Guide fluent reading of the specific task content (e.g., frame, question, problem). Echo the sentence frame: One important text detail is that…

• Model the steps for completing the task. First, I will reread the first paragraph to find one important detail about many breakfast foods students eat. This detail is interesting and important. I’ll highlight it. “Many popular breakfast foods such as cereal and bars are full of sugar.” Please highlight the sentence. Now, you reread the next few sentences to find another important detail to highlight and discuss with your partner.

7. Provide a written and/or verbal model of the desired response/work.

• Display a model response and direct students’ attention. Next, we’ll practice discussing this detail with our starter. Let’s all focus on my example sentence on the board.

• Read aloud the displayed modeled response, then cue echo reading. One important text detail is that many popular breakfast foods are full of sugar. Let’s practice together. One important text detail… is that… many popular breakfast foods… are full of sugar.

8. Build in adequate think time to process, reflect, and prepare for the task.

• Structure uninterrupted think time after cueing students to think of an idea, identify a text detail, react to lesson content, or consider a strategy. Think about two other important details and how you can use the frame to share ideas with your partner.

• Check in to verify that every student has had adequate time to consider a response. Pencils up when you have found two other details.

• Explain any remaining step(s) in the lesson task. You will now take turns sharing what you consider important text details. Partner A, please share first, then B share another detail. Listen carefully to compare and notice if your details are similar or different.

9. Check for understanding of procedural expectations.

• When you check for understanding, avoid asking the unified class “Are there any questions?” or merely directing confused students to seek help from a classmate. Many students, including those learning in a new language, are unlikely to readily admit they need help in front of their peers.

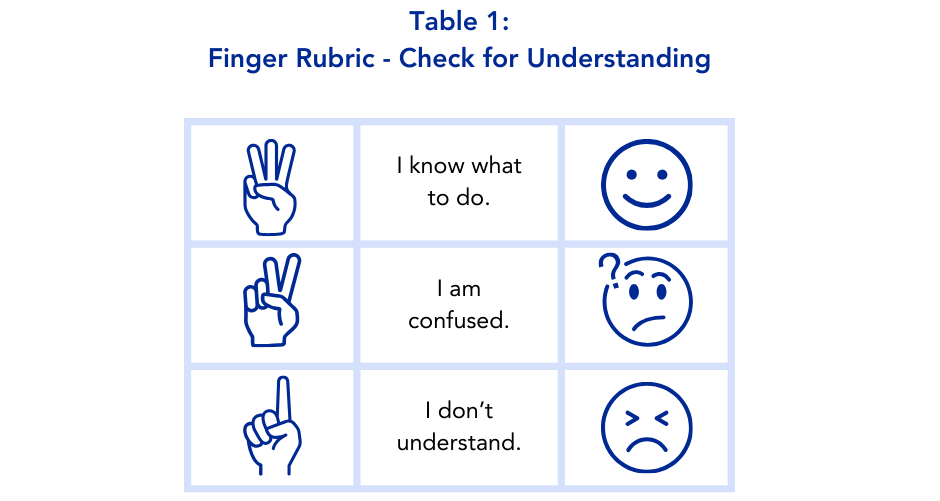

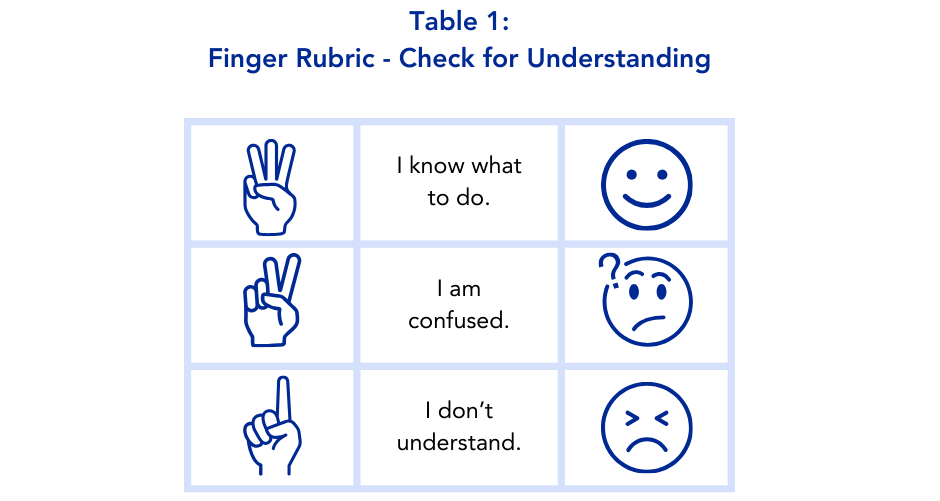

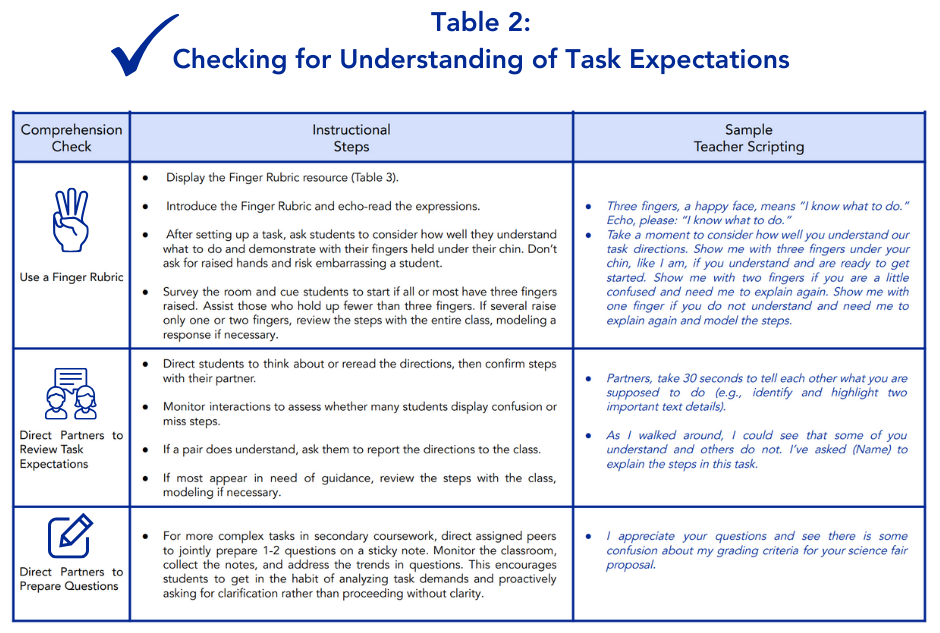

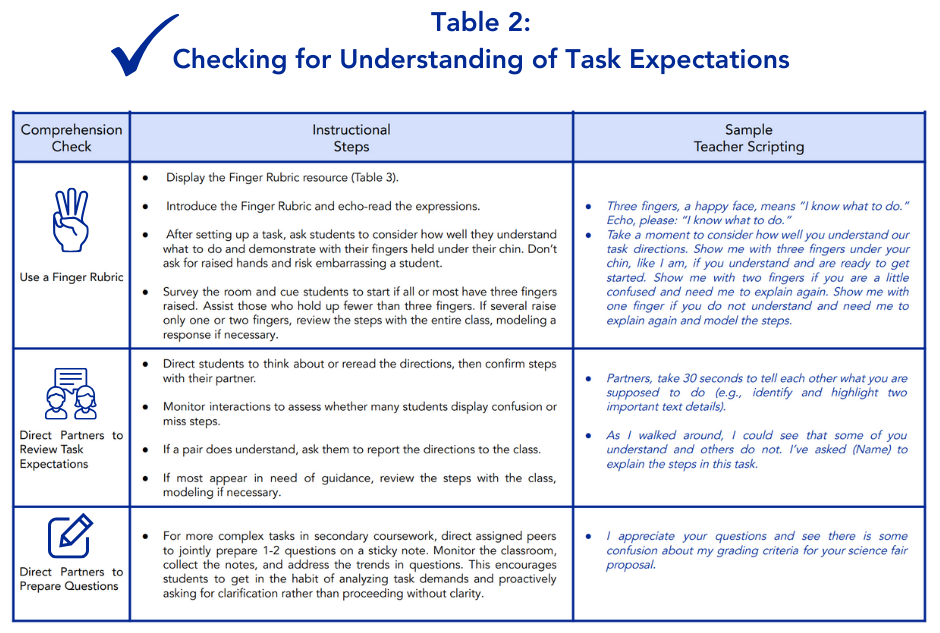

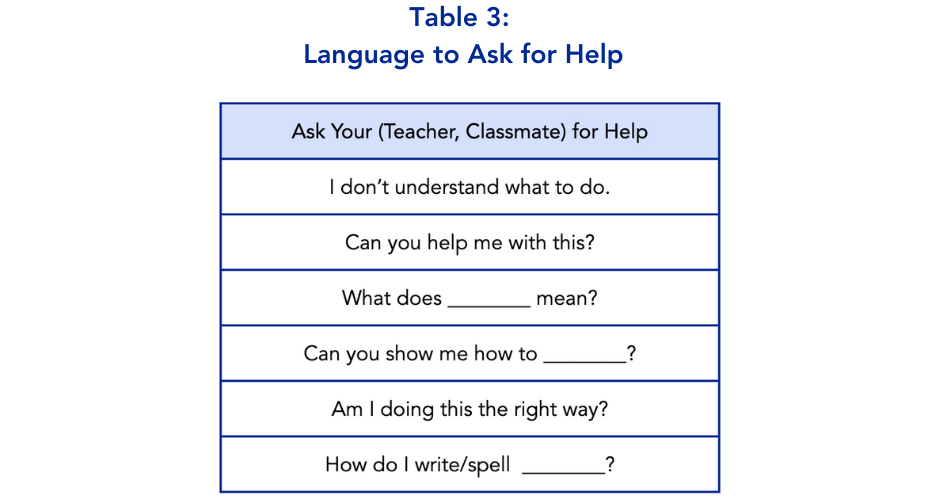

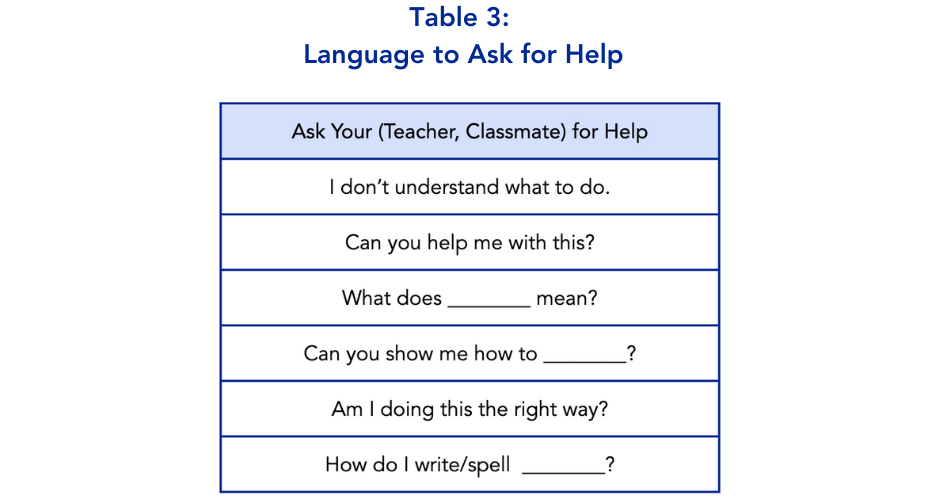

• Use one or two efficient and familiar methods to check whether students understand what you expect them to do. Display a poster prominently with a finger rubric or icons representing levels of understanding. (See Table 1: Finger Rubric.) Show me with your fingers how well you under stand what to do: 3) I understand; 2) I am a little confused; 1) I don’t understand. It looks like you are ready to ex change ideas. (See Table 3: Checking for Understanding of Task Expectations for more detailed guidance.)

10. Provide a clear process and language to ask for help.

• Early in the school year, establish a classroom norm for how to ask for help; for example, raising a hand/pencil or signaling with an assistive device.

• Display and introduce expressions to ask for help. (See Table 2: Language to Ask for Help.) Point out and echo-read relevant expressions for the specific lesson task.

11. Assign an appropriate fast-finisher task.

• Before cueing students to begin an independent or interactive task, provide a brief, related follow-up task for students who finish before their classmates. After you have exchanged important details, be ready to share with the class if your findings were similar or different.

12. Cue students to begin and preview the class/group to confirm all students are off to a productive start.

Concluding Thoughts

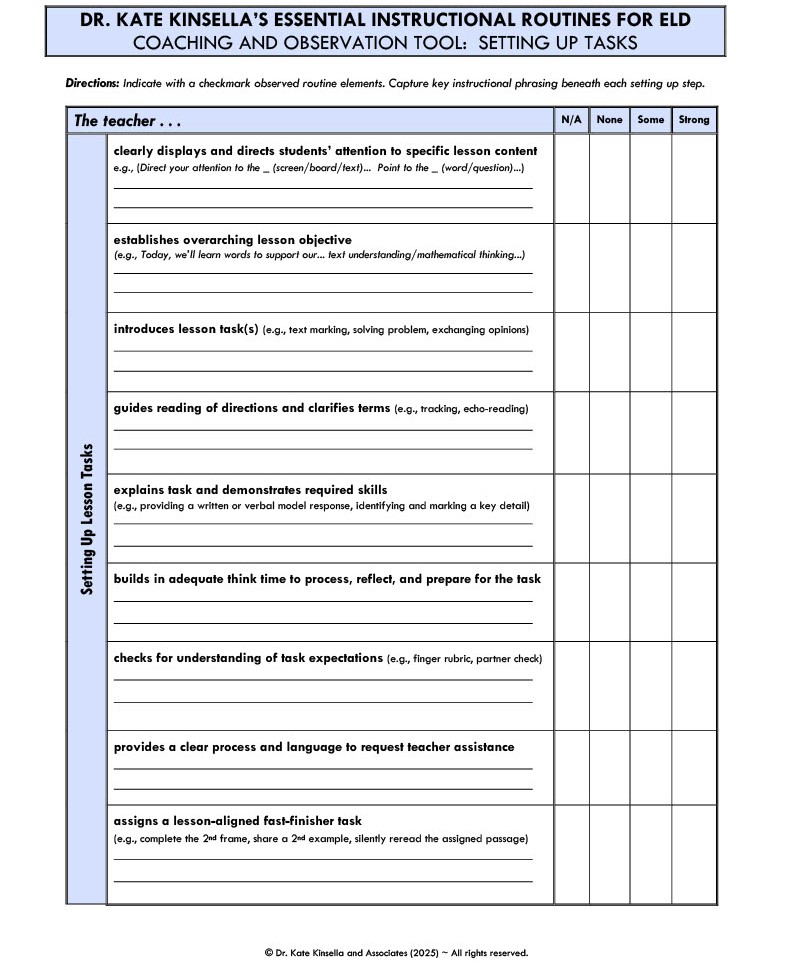

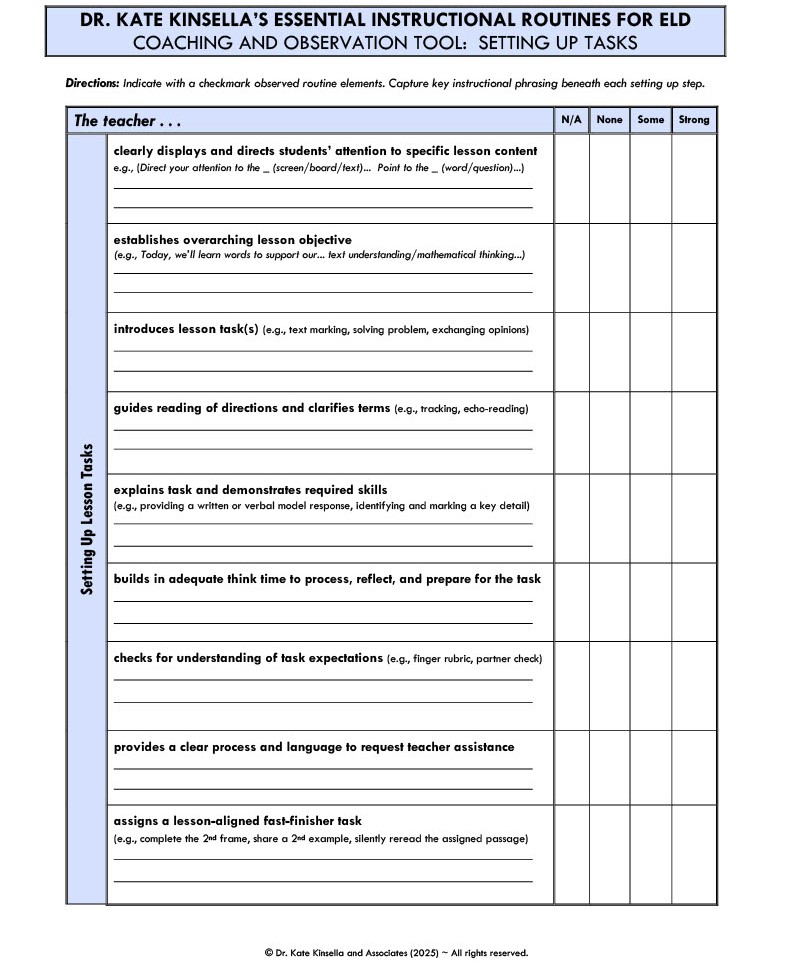

The multistep instructional routine I have introduced for setting up a lesson task has a proven track record of improving student engagement and learning in linguistically diverse classrooms. Multilingual learners at early stages of English proficiency must grapple with challenging core content and literacy tasks across the school day in a language they are newly acquiring. In terms of providing lesson access, a daily priority for every educator should be ensuring our most vulnerable English learners have the guidance and scaffolds to get off to a confident start on essential tasks. The technical coaching tool I have provided in Table 4 was developed to help teachers be more mindful of their task setup and focused as they co-teach or observe a lesson demonstration. I encourage you to introduce this process and the related teaching resources in a staff meeting and to guide observation with a relevant lesson clip. Your colleagues will ideally perceive they have added practical tools to their instructional toolkit, and their multilingual scholars will have much to gain.

References

HMH. (2025). “English 3D: Research Evidence Base.” HMH Education Company.

Kinsella, K. (2024a). “Supporting Multilingual Learners in Developing Reading Fluency Across the School Day.” Language Magazine.

Kinsella, K. (2024b). English 3D Teaching Guide: Grades 2–3. HMH.

Kinsella, K., and Hancock, T. (2018). “A Statistically Significant LTEL Success Story.” Language Magazine.

Kate Kinsella, EdD ([email protected]), has served as the pedagogy guide on three recent US Department of Education–funded research initiatives focused on advancing achievement of K–12 multilingual learners. The author of research-informed curricula supporting English language development and academic literacy, including English 3D and READ 180, she provides professional development and consultancy throughout the US to equip colleagues with understandings and skills to educate MLs with respect and efficacy.