Distance learning is here to stay. Both students and educators were required to quickly pivot to distance platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic without adequate preparation or training (Basilotta-Gomez-Pablos et al. 2022). Many programs elected to keep distance and hybrid learning options for students, with excellent reason. These platforms improve convenience, access, and inclusivity, gaining fast traction. Now, many institutions have an opportunity, or arguably a responsibility, to provide educators with the support needed to be successful while teaching in distance modalities; concurrently, educators are responsible for seeking resources and training to help them leverage technologies to thrive in this distance space (Crompton and Sykora 2021).

The use of technology in distance platforms is important; educators need to navigate a learning platform but don’t necessarily need to become digital technology experts (Crompton and Sykora 2021). So, what is possibly most important? Finding tools that are simple to use and have a high impact. Many educators still report that they do not feel equipped to apply new technologies, although today’s adult learners prefer novel and engaging technology tools (Borte, Nesje, and Lillejord 2023). Therefore, us educators should discuss, introduce, and share these technologies as we discover them to figure this out as a team.

In this article, we will explore how collaborative technologies, specifically collaborative whiteboards, can help bring life to adult learning theories in synchronous learning classrooms.

Students in distance learning platforms often have fewer opportunities to work collaboratively, outside of a break-out-room model, providing challenges for meaningfully applying adult learning theories. Theoretically speaking, collaboration and social engagement are essential components of adult learning, specifically to create a sense of community with learners, which can be more challenging in distance learning classes (Barbetta 2023; Shea, Richardson, and Swan 2022). Additionally, engaging students in more cognitively demanding ways, such as creating, analyzing, or developing information, is especially important to achieve higher-level learning outcomes (Vargas et al. 2024). Therefore, if we can strategically find ways to use digital technologies grounded in adult learning theory, we can strengthen the learning experience, enhance learning outcomes, and bridge the gap between theory and content delivery.

Many digital technologies and platforms exist and are met with opportunities and challenges. Time constraints and cost are common barriers (Borte, Nesje, and Lillejord 2023); therefore, free tools with relatively low preparation are prioritized. The Microsoft Collaborative Whiteboard app, which can be integrated within a Microsoft Teams Meeting space as a screen share, allows students to edit a document or template for more naturalistic collaborations simultaneously. Because it can be integrated into the meeting space, students do not need to download an app, leave the meeting, or switch to a new browser to participate. The form can be prepared before a lesson to allow instructors flexibility in their role and level of scaffolding.

Real-World Examples

A collaborative whiteboard can be applied to various programs, topic areas, or overall aims, and it may also be used as a formative assessment of content delivery. The examples included in this article were used in two separate synchronous occupational therapy courses, one focused on a neuroscience recap of the cranial nerves and one on adapting a therapeutic activity for different levels of traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Pay special attention to the variance between the levels of learning targeted and how this is reflected in the collaborative efforts of the students.

Basic-level Whiteboard

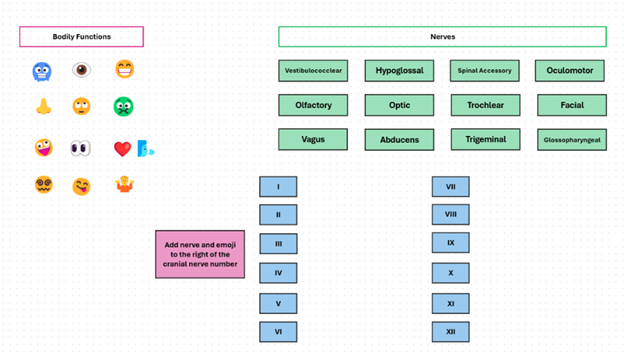

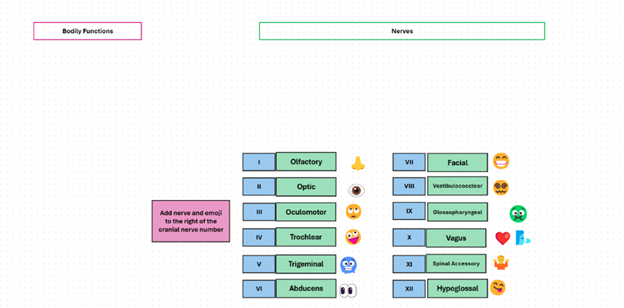

This synchronous whiteboard was used at the beginning of the class session to serve as a formative assessment of the understanding of basic concepts of content. The 24 students were asked to match the function’s cranial nerve name, number, and a representative emoji. This was a more simplistic board that allowed students to reorganize the information presented at a basic knowledge-attainment level collaboratively. It was helpful as a formative assessment to adapt the rest of the lesson according to the students’ level of understanding, and their pace and accuracy of completion. In this case, the students moved their pointers to arrange the information simultaneously, with only a few attempts to collaborate verbally. This activity provided a collaborative effort to complete a joint, goal-oriented task.

Before

After

Advanced-level Whiteboard

The synchronous whiteboard in this example was created for a higher level of application-based learning, where 11 students were asked to alter components of an occupation and treatment modality, baking cookies, to apply to each unique level of traumatic brain injury recovery. This activity demanded greater levels of problem-solving and, therefore, greater levels of collaboration within the class. Many discussions and opportunities for problem-solving and aims for collective approval arose. To close the learning activity, I led a group debrief to discuss each level, provided immediate feedback, and facilitated discussions transferable to other real-world applications. In this example, the directions are in the middle, and the students filled in the sticky notes around the perimeter.

Make it Meaningful

We need buy-in and motivation in higher education. This begins with identifying real-world challenges and ends with reflection. The strategic use of digital technologies, specifically when combined with theoretical reasoning and adult learning principles, can improve classroom experiences through a greater sense of community while targeting higher levels of learning. If we are intentional with this design, educators can increase student engagement and facilitate higher levels of learning in synchronous online classrooms. Sprinkle goal-oriented and real-world relevant material on top, and you have a recipe for a meaningful outcome.

Looking Ahead

With institutions more widely embracing long-term implementation of distance education programs, faculty require ongoing support, training, and access to resources for sustained confidence and success. Dissemination of practical examples of use by peer educators and texts outlining an approach to identify and develop materials will benefit ongoing efforts to increase competency. In other words, we must keep each other informed on educational tech-gems we find to collectively improve our system.

How to Whiteboard: Quick Start Guide

- Open Microsoft Teams

- Click on the Whiteboard tab in your meeting space

- Upload an editable template or create a blank canvas

- Once in your meeting, share your screen and select the whiteboard app

- Scaffold your task with prompts and questions

Jaimee Fielder, OTD, OTR is an Assistant Professor of Occupational Therapy at the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences. She earned her Master of Science in Occupational Therapy from Touro University Nevada, Post-Professional Doctorate in Occupational Therapy from Texas Woman’s University, and is now pursuing a Doctorate in Education from the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, with a dissertation focused on educational technology and active learning in higher education classrooms.

References

Barbetta, Patricia M. 2023. “Technologies as Tools to Increase Active Learning During Online Higher-Education Instruction.” Journal of Educational Technology Systems 51(3): 317–339.

Basilotta-Gomez-Pablos, Verónica, Matarranz, María, Casado-Aranda, Luis A., and Otto, Andreas. 2022. “Teachers’ Digital Competencies in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 19(8).

Børte, Kristi, Nesje, Kjersti, and Lillejord, Sølvi. 2023. “Barriers to Student Active Learning in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 28(3): 597–615.

Crompton, Helen, and Sykora, Christopher. 2021. “Developing Instructional Technology Standards for Educators: A Design-Based Research Study.” Computers and Education Open 2: 100044.

Shea, Peter, Richardson, Jennifer, and Swan, Karen. 2022. “Building Bridges to Advance the Community of Inquiry Framework for Online Learning.” Educational Psychologist 57(3): 148–161.

Vargas, Jesús H., Ojeda, Edison C. C., Zapata, Carlos A. C., Flores, Karen A. A., Vela, Juan A. H., and Espinoza, Yessenia E. D. 2024. “Analysis of Significant Learning in Higher Education: Usefulness of Fink’s Taxonomy: A Systematic Review.” Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research 7(S7): 1341.