Students may feel lonely, and faculty can feel overwhelmed even in well-designed online classes; however, a focus on engagement and well-being educators can support faculty and students via simple, low-tech, and personalized strategies in conjunction with the learning platform. This article will share practical tips to help faculty support their wellbeing and improve student engagement in the online environment, especially at the stressful end of a semester.

A focus on engagement is a beloved concept that educators have embraced for decades. Chickering and Gamson (1987) remind us about the importance of participation and engagement in the classroom: “Learning is not a spectator sport. Students do not learn much just sitting in classes listening to teachers, memorizing pre-packaged assignments, and spitting out answers. They must talk about what they are learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences, and apply it to their daily lives” (p. 4). Similarly, we think Chickering and Gamson’s approach to teaching applies to the modern day online classroom. Faculty and students need to work together to foster engagement in online spaces. Learning does not occur in isolation.

When Online Teaching Becomes Overwhelming

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2022), in 2021 most institutions offered remote instruction, hybrid instruction, face-to face instruction, or some combination of these modalities. Many studies have looked at ways to ensure the quality of online courses, providing general suggestions for best practices in the online environment (McNeal & Gray, 2021). However, how do we ensure we are meeting the wellbeing needs for faculty and students within the online platform, especially given the recent volume of online use? We need to find ways to teach, learn, and find the often-elusive work-life balance to slow down and meet faculty needs and improve student engagement.

Many faculty are often unprepared for the volume of work that comes with teaching online. Online courses can quickly become overwhelming as the emails, discussion posts, and papers roll in like the next COVID-19 variant. Time management techniques can ensure success and wellbeing because many faculty are in a state of “time poverty” (Berg & Seeber, 2016, p. 7). Faced with the challenge of having too much to do, faculty are impoverished as they rush to create course content and respond to emails. While we may not have control over class sizes or course loads, we can manage our workspace, habits, and course procedures.

Simple Course Design Supports Student Success

Darby (2019) writes about how students can easily become overwhelmed by online classes and may struggle using the institution’s portal or LMS. Organizing your class in a way that is simple, consistent, and straightforward will help alleviate student anxiety. For example, have all response postings due on a Tuesday at noon. Name all of your files in a consistent manner, for example “Reading 1, Week 1.” In addition to a welcome video at the start of the course, create a video for the ending of the course to share good wishes and final thoughts.

Low-Tech, Personalized Strategies That Work

Low-tech is not the enemy. While we might be tempted to think that a fancier high tech item is superior, in many cases this option is not the best choice overall. For example, during the COVID pivot, many institutions’ first reactions were to seek out a new type of technology to provide services to students, such as new conferencing software that could be used to project faculty into multiple classrooms simultaneously. While new technology can be innovative and fun, it often comes with a high price tag and a need for new professional development during a time of fatigue. Instead, do not rule out the low-tech option for a solution. At our institution, low-tech and familiar options like phone calls and photos worked well to meet students’ needs for immediate feedback with a low level of stress.

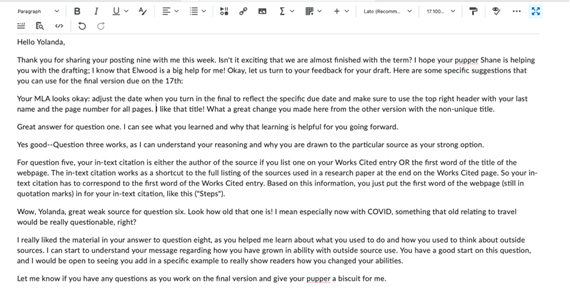

We’d like to share some examples of personalized actual course documents feedback that contribute to decreased stress levels for students and faculty. Here follows feedback from the end of the term that uses first names and conversational tone as a stress-relieving option:

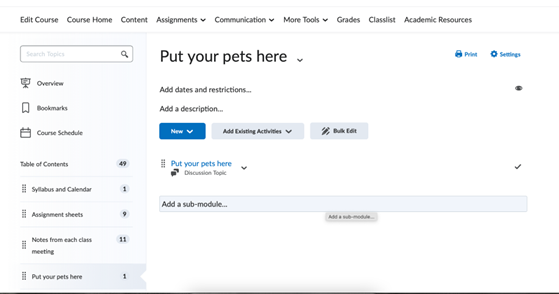

Another strategy is to use low-stakes assignments to get students comfortable with the technology, which can be vital if new technology is needed for final exams or end-of-term assignments. In this example below, Dr. Gray created a “Put your pets here” discussion posting topic that encouraged students to learn the skills of the LMS, such as posting an image, responding to classmates, reading the responses, in a low-stakes approach. The skills are learned in a fun manner, so that at the end of the term when a document might need to be loaded, the class can reflect back on the fun example.

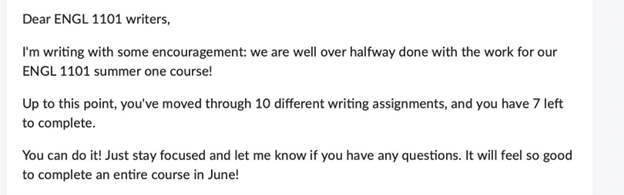

Faculty can also use announcements to show encouragement and progress for students. As in the example below, sometimes sharing progress, such as how far they are in the course, can help students stay motivated and engaged near the end of the semester.

Faculty can utilize the features of the LMS to identify students who are at risk, which becomes critical toward the end of the semester. For example, look at the log in records. Has a student been missing for more than 2 days? Does a student click on a link but the logs show they only looked at the directions for a complex assignment for 30 seconds? Reach out to students with a personalized email and try to get them back on track. Not only will this action show care, but it might prevent a simple slip from turning into a crisis.

Boundaries, Balance, and a Slower Pace

Faculty should promote their wellbeing by setting boundaries with home/work balance. An online class can have a constant presence in your work life and your home life, as access is just a click away. Most educators worked at home for a time period during COVID, and the lines between home time and work time blurred, increasing possibilities for burnout. Carving out time to rest and recharge helps us return to work in a more rejuvenated state. One way to create this boundary is to make it clear to supervisors and students that unless there is a critical emergency, there will be no responses to emails or grading during a set time of hours, such as between 7pm and 7am. Vow to work slowly, diligently, and thoughtfully, taking a cue from the author and conchologist Elizabeth Bailey (2016): “A last look at the stars and then to sleep. Lots to do at whatever pace I can go. I must remember the snail. Always remember the snail” (p. 161).

In conclusion, taking time and care to work together to cultivate joyful connections with our students and being present in the moments of instruction no matter the format can result in supportive and positive learning experiences. Online instruction should not simply be a robotic production that pushes through to a product. A slower and more deliberate pace can help teachers and students reflect and act with purpose to encourage “emotional and intellectual resilience” no matter what lies ahead of them (Berg & Seeber, 2017, p. ix). Let us slow down and help students connect themselves to their work, their teachers, and their fellow learners.

Dr. Jennifer P. Gray is a professor of English and the creator and director of the Writing Center at the College of Coastal Georgia. She has taught writing courses for more than 20 years, and she is passionate about encouraging student success for any writing occasion.

Dr. Lisa McNeal is the Director of eLearning at the College of Coastal Georgia. She also teaches online and is passionate about supporting faculty as they integrate technology into their teaching process.

References

Bailey, E. T. (2016). The sound of a wild snail eating. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Berg, M., & Seeber, B. K. (2017). The slow professor: Challenging the culture of speed in the academy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Chickering, A., & Gamson, Z. (1987). “Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education.” AAHE Bulletin, 39, no. 7: 3-7.

Darby, F., & Lang, J. M. (2019). Small teaching online: Applying learning science in online classes. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

McNeal, L., & Gray, J. (2019). A new spin on quality: Broadening online course reviews through coaching and slow thinking. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 22(4).

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Fast Facts. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372